Every writer procrastinates. Even John McPhee, one of the most prolific writers of our time. “I’ll go hours before I’m able to write a word,” he has said. “I’ll make tea. I mean, I used to make tea all day long.”

I don’t know any writer who doesn’t suffer the same affliction frequently — if not daily. But when a looming deadline thwarts your tea party, you need ways to beat procrastination. Here are five life hacks for those times when you’re struggling to get started:

1. Compose an email.

Open up your email and write a note to a friend, explaining all the reasons you’re excited about writing this piece. There’s something about composing in an email template that’s less daunting than facing a blank page. I often cut and paste from these emails into a Word document, so I don’t have to stare down the void. Part of the reason I think the email trick works so well is that you’re writing for a specific, friendly audience. When we sit down to write, we often imagine our critics, peers, or rivals looking over our shoulders. Or, even worse, we’re ignoring our audience completely and writing self-indulgent crap that could only possibly interest ourselves. (Sometimes you have to write that stuff, too; just remember to cut it in revision.)

2. Switch to handwriting.

Sometimes the delete key is not your friend. If you find yourself self-editing in the middle of a sentence even as you are composing it — STOP! Step away from the computer. Get out a notebook or a piece of paper and a pen. And just write. Write forward. Don’t worry if it’s bad (no one else has to see it). Don’t stop (or edit) until you’ve filled the page. Then go back and mine what you’ve written for the nuggets of brilliance hidden in the sludge. Type those nuggets into the fresh Word document that’s been mocking you, and then use that momentum to carry you forward. As Anne Lamott taught me in “Bird by Bird,” the Shitty First Draft is your friend, not your enemy.

3. Make a map.

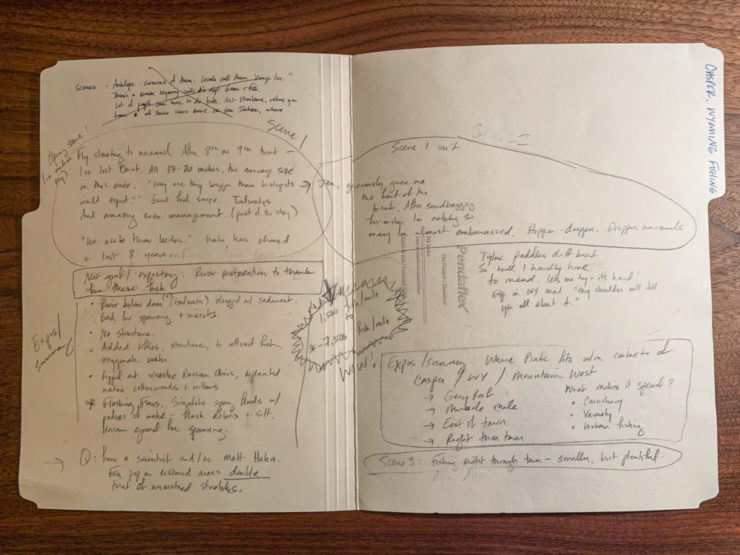

I hesitate to use the word “outline,” which resurrects bad memories of high school versions with Roman numerals and capital letters and standard numerals and lowercase letters. So let’s call it a story map. It can look like a flow chart, a drawing, or a blueprint. It can simply be a list of things you need to get into the piece. It can be a pile of notecards that you rearrange on the floor, or tape to a closet door. One recent story, a fishing essay, started out this way, on the inside of a manila folder holding my notes and interviews:

A story map for Kim Cross' essay on fly fishing

Only when I had it all there in front of me did I realize that my opening scene was irrelevant to the rest of the piece. So I threw it out and used another Anne Lamott concept I learned from Bird by Bird: the one-inch picture frame.

A "one-inch frame," as taught by Anne Lamott, helped Kim Cross zero in on a tight scene for a fly-fishing essay.

When you’re overwhelmed, just write what you can see through a one-inch frame. My new opening image would literally fit there: a fly-fishing fly coming unraveled after hauling in eight big trout.

4. Pirate other leads.

Many writers struggle to gain momentum until they’ve nailed the lead. Which can make starting the most painful part of the writing process. Guess what? You can’t plagiarize structure. So instead of starting from scratch, revisit stories you admire and study the bones — especially the leads — and look for a model that suits your story.

“When you’re stuck, ruffle through all those anthologies and read the first graph or two of 10 or 20 stories,” says Glenn Stout, series editor of Best American Sports Writing. “Not that you’ll copy one (at least, not precisely), but it will shake you out of the corner you’ve worked yourself into, and spark a new way of getting into a story. It just might make something click and you’ll come up with an entry point you hadn’t considered.”

“Shotgunning leads,” as Stout calls it, can be a powerful rut-buster, a way of ensuring you’re not using the same lead over and over. “We all fall into patterns, whether we recognize them or not, and this is one way to make sure that doesn’t happen,” says Stout, author of “Young Woman and the Sea” and dozens of other books. “I find it particularly useful when working on books — I don’t want to repeat myself in the ways I start a chapter.” Hear him riff on shotgunning leads and other writing tips in this episode of The Creative Nonfiction Podcast with Brendan O’Meara.

An hourglass keeps Kim Cross committed to writing in set time intervals

5. Do timed intervals.

Borrow the concept of “fartleks” a Swedish running technique that involves spotting a mailbox or other visual goal and picking up the pace until you reach it and earn a rest interval (until the next mailbox). The writer’s version involves a timed butt-in-chair interval — usually 30 minutes or an hour – and a focused mental sprint during which you’re not allowed to check email, make tea, or do anything but write. When the time’s up, reward yourself with a short break.

I swear by an hourglass. It makes the passage of time more visceral. And it helps me hold myself to honest hour’s work. If I must run to the bathroom or answer the phone, I “pause” it by tipping it on its side. After finding my sand timer trick, I learned about the Pomodoro Technique, developed in the 1980s by an Italian named Francesco Cirillo, who created a system that used a tomato-shaped egg timer to boost his productivity. But that system has a few more steps and rules, and I think an hourglass is way sexier than a tomato-shaped egg timer.