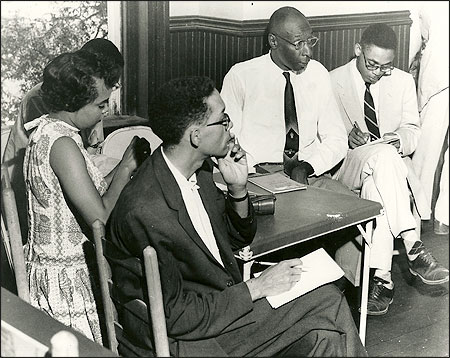

Simeon Booker, a 1951 Nieman Fellow and a legendary civil rights reporter who headed the Washington bureau for Jet and Ebony magazines for five decades, died in Solomons, Maryland on December 10. He was 99.

The first full-time black reporter for The Washington Post, Booker was best known for his civil rights coverage for Jet and Ebony. He helped bring to a national audience the story of 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African-American teen from Chicago who—while visiting relatives in Mississippi—was brutally killed by white men after allegedly whistling at a white woman. (That woman in 2007 told an author working on a book about the murder that Till never made any advances toward her.) Booker was in Chicago when he learned of Till’s death, and was with the boy’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, when she was at the funeral home and insisted her son’s casket be open to show his mutilated corpse. Booker’s account of the funeral, as well as photographs of the open casket published in Jet and other African American publications, made Till an icon of the civil rights movement.

Booker covered the trial of Till’s accused killers, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam. The pair were acquitted by an all-white jury but later admitted to the murder in a paid interview with Look magazine. Booker wrote in an account for Nieman Reports that “the murder and everything about it had a galvanizing and enduring impact on the civil rights movement, which in turn changed everything about life in America, including its journalism.”

Born in Baltimore, Maryland and raised in Youngstown, Ohio, Booker began his journalism career while attending Virginia Union University, writing about the Negro Baseball League for the Youngstown Vindicator. After graduating with an English degree in 1942, he worked at the Baltimore Afro-American before becoming the second black Nieman Fellow in 1950. He joined The Washington Post following his fellowship, and was subsequently hired by Johnson Publishing Co.—which published both Jet and Ebony—in 1954. He stayed with the company until his retirement in 2007; during his many years there, he continued to document the civil rights movement despite threats, sometimes posing as a minister or sharecropper. He covered the Freedom Ride from Washington to New Orleans in 1961, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. One of the few black reporters in D.C. at the time, Booker covered 10 U.S. presidents and reported on the Vietnam War from Southeast Asia.

Booker was also the author of many books, including “Black Man’s America” and “Shocking the Conscience: A Reporter’s Account of the Civil Rights Movement,” a 2013 memoir co-written with his wife Carol McCabe Booker.

Among his many recognitions, Booker was the first African-American journalist to win the National Press Club’s Fourth Estate Award for lifetime achievement in 1982, and was the recipient of the George Polk Career Award in 2015. He was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists’ Hall of Fame in 2013, and, in 2017, Ohio representatives introduced legislation to award Booker the Congressional Gold Medal.

Booker is survived by his wife Carol, sons Simeon III and Theodore, daughter Theresa, and several grandchildren.

The first full-time black reporter for The Washington Post, Booker was best known for his civil rights coverage for Jet and Ebony. He helped bring to a national audience the story of 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African-American teen from Chicago who—while visiting relatives in Mississippi—was brutally killed by white men after allegedly whistling at a white woman. (That woman in 2007 told an author working on a book about the murder that Till never made any advances toward her.) Booker was in Chicago when he learned of Till’s death, and was with the boy’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, when she was at the funeral home and insisted her son’s casket be open to show his mutilated corpse. Booker’s account of the funeral, as well as photographs of the open casket published in Jet and other African American publications, made Till an icon of the civil rights movement.

Booker covered the trial of Till’s accused killers, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam. The pair were acquitted by an all-white jury but later admitted to the murder in a paid interview with Look magazine. Booker wrote in an account for Nieman Reports that “the murder and everything about it had a galvanizing and enduring impact on the civil rights movement, which in turn changed everything about life in America, including its journalism.”

Born in Baltimore, Maryland and raised in Youngstown, Ohio, Booker began his journalism career while attending Virginia Union University, writing about the Negro Baseball League for the Youngstown Vindicator. After graduating with an English degree in 1942, he worked at the Baltimore Afro-American before becoming the second black Nieman Fellow in 1950. He joined The Washington Post following his fellowship, and was subsequently hired by Johnson Publishing Co.—which published both Jet and Ebony—in 1954. He stayed with the company until his retirement in 2007; during his many years there, he continued to document the civil rights movement despite threats, sometimes posing as a minister or sharecropper. He covered the Freedom Ride from Washington to New Orleans in 1961, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. One of the few black reporters in D.C. at the time, Booker covered 10 U.S. presidents and reported on the Vietnam War from Southeast Asia.

Booker was also the author of many books, including “Black Man’s America” and “Shocking the Conscience: A Reporter’s Account of the Civil Rights Movement,” a 2013 memoir co-written with his wife Carol McCabe Booker.

Among his many recognitions, Booker was the first African-American journalist to win the National Press Club’s Fourth Estate Award for lifetime achievement in 1982, and was the recipient of the George Polk Career Award in 2015. He was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists’ Hall of Fame in 2013, and, in 2017, Ohio representatives introduced legislation to award Booker the Congressional Gold Medal.

Booker is survived by his wife Carol, sons Simeon III and Theodore, daughter Theresa, and several grandchildren.