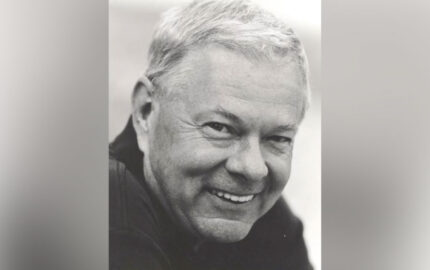

Robert Timberg, Marine, reporter, editor, acclaimed author and Nieman Fellow in the class of 1980, died on September 6 in Annapolis, Maryland, of respiratory failure. He was the bravest man I ever met.

Shockingly disfigured by a land mine that blew off his face when he had only 13 days left in his tour of Vietnam, he endured 35 reconstructive operations. He took the title of his last book, “Blue-Eyed Boy,” an achingly personal memoir, from an e.e. cummings poem that read:

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

How do you like your blue-eyed boy

Mister Death

At Harvard, we hung out. He never once mentioned Vietnam.

Oddly, he chose one of the most public of careers, journalism, in the most visible of venues, Washington. He turned out to be good at it. He was a reporter’s reporter. He hated show-offs and “bullshit, self-help” articles and books. As a Nieman, he loved Richard Neustadt’s “Uses of History” class and reveled in watching the (blessedly few) Harvard students who would try to pontificate about, say, Roosevelt’s First Hundred Days, without knowing how few of Roosevelt’s famous legislative measures were actually enacted by mid-June 1933.

During Nieman seminars, when the questions veered toward “accommodating cocktail party chatter,” in the words of Paul Lieberman, Bob was the Nieman who most often asked tough questions.

He was friendly with the entire Nieman class but gravitated toward the “foreign” Niemans—Suthichai Yoon, whose English-language newspaper, the Nation, in Thailand was continually threatened with being shut down for its fearless reporting; Daniel Passent, who was the political columnist for Politiza, the chief newsmagazine in Poland as the Communist party clung to power; and South African Aggrey Klaaste, who never walked out of a room without automatically checking his back pocket to make certain that he hadn’t forgotten his “pass.”

Bob and I attended a feast one night put on by Daniel Passent’s visiting wife, Agnieszka Osiecka, a wildly popular Polish poet and composer of more than 2,000 songs. As Agnieszka prepared caviar on tiny toast squares, she instructed us on how to handle a forgotten dinner invitation: Dress up to the hilt on the following night, buy flowers, and descend on the home of the forgotten party as if the host had forgotten the occasion.

Timberg said he decided to become a journalist almost as a fluke—his wife told him he had written good letters from Vietnam. He got a master’s degree from Stanford University, and eventually landed a job on the Annapolis Evening Capital—without ever publishing a word, or learning to type.

He had finished his Nieman and had risen to White House correspondent for the Baltimore Sun when he wrote “The Nightingale’s Song,” profiling his fellow Naval Academy grads who had become leading figures in the government during the Reagan years. The anti-war fervor of Vietnam had never worn off. Vietnam vets were still suspect in many quarters, but Timberg’s deeply researched journalistic account of John McCain’s ordeal as a prisoner of war in Vietnam changed many minds, including mine.

In his last book, “Blue-Eyed Boy,” published in 2014, he finally wrote about his wounds. It drew on all the threads of his extraordinary life—his great writing talent, his wide reading, his energy, fundamental kindness, competitiveness, smarts and yes, bravery, to tell the story of, in his words, “how I decided not to die.”

He reluctantly agreed to be the master of ceremonies when the National Endowment for the Humanities launched what by that time had become the obligatory federal veterans program for those returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This self-controlled, acclaimed author whose book exemplified transparency and openness looked out over a sea of high-level officials of government agencies and lost it.

He asked, “Where the fuck were you when WE came home.”

Shockingly disfigured by a land mine that blew off his face when he had only 13 days left in his tour of Vietnam, he endured 35 reconstructive operations. He took the title of his last book, “Blue-Eyed Boy,” an achingly personal memoir, from an e.e. cummings poem that read:

Jesus

he was a handsome man

and what i want to know is

How do you like your blue-eyed boy

Mister Death

At Harvard, we hung out. He never once mentioned Vietnam.

Oddly, he chose one of the most public of careers, journalism, in the most visible of venues, Washington. He turned out to be good at it. He was a reporter’s reporter. He hated show-offs and “bullshit, self-help” articles and books. As a Nieman, he loved Richard Neustadt’s “Uses of History” class and reveled in watching the (blessedly few) Harvard students who would try to pontificate about, say, Roosevelt’s First Hundred Days, without knowing how few of Roosevelt’s famous legislative measures were actually enacted by mid-June 1933.

During Nieman seminars, when the questions veered toward “accommodating cocktail party chatter,” in the words of Paul Lieberman, Bob was the Nieman who most often asked tough questions.

He was friendly with the entire Nieman class but gravitated toward the “foreign” Niemans—Suthichai Yoon, whose English-language newspaper, the Nation, in Thailand was continually threatened with being shut down for its fearless reporting; Daniel Passent, who was the political columnist for Politiza, the chief newsmagazine in Poland as the Communist party clung to power; and South African Aggrey Klaaste, who never walked out of a room without automatically checking his back pocket to make certain that he hadn’t forgotten his “pass.”

Bob and I attended a feast one night put on by Daniel Passent’s visiting wife, Agnieszka Osiecka, a wildly popular Polish poet and composer of more than 2,000 songs. As Agnieszka prepared caviar on tiny toast squares, she instructed us on how to handle a forgotten dinner invitation: Dress up to the hilt on the following night, buy flowers, and descend on the home of the forgotten party as if the host had forgotten the occasion.

Timberg said he decided to become a journalist almost as a fluke—his wife told him he had written good letters from Vietnam. He got a master’s degree from Stanford University, and eventually landed a job on the Annapolis Evening Capital—without ever publishing a word, or learning to type.

He had finished his Nieman and had risen to White House correspondent for the Baltimore Sun when he wrote “The Nightingale’s Song,” profiling his fellow Naval Academy grads who had become leading figures in the government during the Reagan years. The anti-war fervor of Vietnam had never worn off. Vietnam vets were still suspect in many quarters, but Timberg’s deeply researched journalistic account of John McCain’s ordeal as a prisoner of war in Vietnam changed many minds, including mine.

In his last book, “Blue-Eyed Boy,” published in 2014, he finally wrote about his wounds. It drew on all the threads of his extraordinary life—his great writing talent, his wide reading, his energy, fundamental kindness, competitiveness, smarts and yes, bravery, to tell the story of, in his words, “how I decided not to die.”

He reluctantly agreed to be the master of ceremonies when the National Endowment for the Humanities launched what by that time had become the obligatory federal veterans program for those returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. This self-controlled, acclaimed author whose book exemplified transparency and openness looked out over a sea of high-level officials of government agencies and lost it.

He asked, “Where the fuck were you when WE came home.”