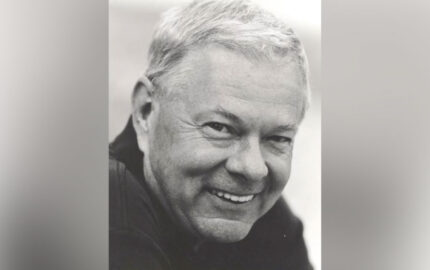

William Marimow, a 1983 Nieman Fellow, remembers his Philadelphia Inquirer colleague Acel Moore, a 1980 Nieman Fellow, who died on February 12 at age 75. Moore was a co-founder of the National Association of Black Journalists and a champion of diversity during his 43 years at the Inquirer.

When I think of Acel Moore, the great Philadelphia Inquirer newsman who died on Friday night, I remember a colleague whose influence permeated the pages of the Inquirer and the hearts and minds of our staff. In countless ways—some highly visible and not to be forgotten like his 1976 series on violence by guards at the Farview State Mental Hospital; others, barely recalled but so permanently important that a talented Daily News editor will never forget the call he placed to get her an internship in 1987 when she was a shy student at Cabrini College—Acel profoundly shaped the issues that the Inquirer covered and the staff we hired to cover them.

I first met Acel in the summer of 1972 when I joined the newspaper as an assistant to our economics columnist and a business reporter. It was a newsroom hurtling through a transition from the ownership of Walter Annenberg to the corporate ownership of Knight Newspapers. Like me, Acel was a native son—born and raised in Philadelphia. But unlike me, a child of the suburbs—specifically Havertown—Acel had grown up in South Philadelphia, graduated from Overbrook High School—hard by Larry’s Cheesesteaks, “home of the bellyfiller”—and by virtue of covering the police, he knew every nook and cranny of the city. He knew the cops, the firefighters in neighborhood station houses, pastors of the city’s churches, activists and pacifists, and his friends and neighbors from childhood.

From the outset of our friendship, Ace—as I called him—was a generous and expansive colleague, always willing to share information, sources, a yarn about his journalistic exploits and a laugh. When I covered the labor beat in the years before the Farview story propelled his work to wide acclaim, we sat back to back, no more than three feet apart in a newsroom filled with cigarette smoke constantly wafting in the air and the clatter of typewriters and wire machines creating an incessant din.

In the years that followed, Acel was always a source of inspiration and information: In December 1983, when I was back in the newsroom after a Nieman fellowship and searching in desperation for a good story, Acel urged me to talk with Matthew Horace, the son of a longtime friend, who had been mauled by a police K-9 dog when he came downtown to celebrate the Sixers’ NBA championship. That led to more than 40 stories about a small group of officers whose dogs had attacked innocent and unarmed citizens. And thanks to Acel’s guidance, it changed the way K-9 officers deployed their dogs for a generation. (See the Winter 1984 issue of Nieman Reports for details.)

When the Goode administration dropped a bomb on the MOVE house on May 13, 1985, killing 11 people and destroying the neighborhood, it was Acel who guided me to sources and documents that helped the Inquirer understand what had happened on that tragic day on Osage Ave. I can still vividly remember him showing me a detailed report documenting the weaponry that the Police Department brought to Osage Ave. for the siege that ensued and wondering why anyone would need a .50-caliber machine gun and Uzis to remove the radical group from a row house.

When I returned to Philadelphia as the editor of the Inquirer after 13 years away, one of my first public speaking engagements was to greet more than 50 student journalists from Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania suburbs, and south Jersey. They were all high school students, most of them minorities, and they were dedicating most of two months of Saturdays to learning the craft of journalism from Inquirer staffers teaching at the Acel Moore Career Development Workshops.

Throughout his long career, Acel’s commitment to making sure that our newsroom recognized the stories of underprivileged and under-covered Philadelphians was unwavering. He was ardent in his efforts to make sure that the Inquirer and the Daily News hired, trained, and retained African-American and other minority journalists so that our coverage could reflect the issues that most affected Philadelphians of all races in every neighborhood and in every economic class. I’m sure that if Acel were reading these words today, he would say firmly and sternly: “Bill, we have to do a lot better.” Because of Acel Moore’s work, the city and the Inquirer is better, but—as Acel well knew—a lot of work is still to be done.

When I think of Acel Moore, the great Philadelphia Inquirer newsman who died on Friday night, I remember a colleague whose influence permeated the pages of the Inquirer and the hearts and minds of our staff. In countless ways—some highly visible and not to be forgotten like his 1976 series on violence by guards at the Farview State Mental Hospital; others, barely recalled but so permanently important that a talented Daily News editor will never forget the call he placed to get her an internship in 1987 when she was a shy student at Cabrini College—Acel profoundly shaped the issues that the Inquirer covered and the staff we hired to cover them.

I first met Acel in the summer of 1972 when I joined the newspaper as an assistant to our economics columnist and a business reporter. It was a newsroom hurtling through a transition from the ownership of Walter Annenberg to the corporate ownership of Knight Newspapers. Like me, Acel was a native son—born and raised in Philadelphia. But unlike me, a child of the suburbs—specifically Havertown—Acel had grown up in South Philadelphia, graduated from Overbrook High School—hard by Larry’s Cheesesteaks, “home of the bellyfiller”—and by virtue of covering the police, he knew every nook and cranny of the city. He knew the cops, the firefighters in neighborhood station houses, pastors of the city’s churches, activists and pacifists, and his friends and neighbors from childhood.

From the outset of our friendship, Ace—as I called him—was a generous and expansive colleague, always willing to share information, sources, a yarn about his journalistic exploits and a laugh. When I covered the labor beat in the years before the Farview story propelled his work to wide acclaim, we sat back to back, no more than three feet apart in a newsroom filled with cigarette smoke constantly wafting in the air and the clatter of typewriters and wire machines creating an incessant din.

In the years that followed, Acel was always a source of inspiration and information: In December 1983, when I was back in the newsroom after a Nieman fellowship and searching in desperation for a good story, Acel urged me to talk with Matthew Horace, the son of a longtime friend, who had been mauled by a police K-9 dog when he came downtown to celebrate the Sixers’ NBA championship. That led to more than 40 stories about a small group of officers whose dogs had attacked innocent and unarmed citizens. And thanks to Acel’s guidance, it changed the way K-9 officers deployed their dogs for a generation. (See the Winter 1984 issue of Nieman Reports for details.)

When the Goode administration dropped a bomb on the MOVE house on May 13, 1985, killing 11 people and destroying the neighborhood, it was Acel who guided me to sources and documents that helped the Inquirer understand what had happened on that tragic day on Osage Ave. I can still vividly remember him showing me a detailed report documenting the weaponry that the Police Department brought to Osage Ave. for the siege that ensued and wondering why anyone would need a .50-caliber machine gun and Uzis to remove the radical group from a row house.

When I returned to Philadelphia as the editor of the Inquirer after 13 years away, one of my first public speaking engagements was to greet more than 50 student journalists from Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania suburbs, and south Jersey. They were all high school students, most of them minorities, and they were dedicating most of two months of Saturdays to learning the craft of journalism from Inquirer staffers teaching at the Acel Moore Career Development Workshops.

Throughout his long career, Acel’s commitment to making sure that our newsroom recognized the stories of underprivileged and under-covered Philadelphians was unwavering. He was ardent in his efforts to make sure that the Inquirer and the Daily News hired, trained, and retained African-American and other minority journalists so that our coverage could reflect the issues that most affected Philadelphians of all races in every neighborhood and in every economic class. I’m sure that if Acel were reading these words today, he would say firmly and sternly: “Bill, we have to do a lot better.” Because of Acel Moore’s work, the city and the Inquirer is better, but—as Acel well knew—a lot of work is still to be done.