For 30 of his 42 years at The Globe and Mail, three weekly columns were influential in determining a book's success.

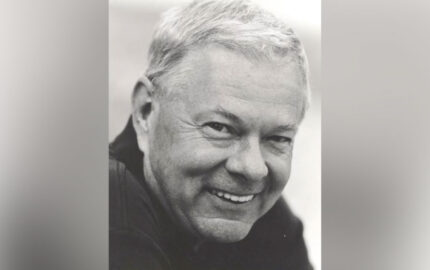

Although his byline disappeared with his retirement more than 20 years ago, former Globe and Mail literary editor William French is still remembered by former colleagues and literary admirers as a giant of his day — Canada's dominant literary critic during a formative period of the national literature.

French, who died in Toronto last Tuesday at the age of 86, left the first graduating class of the University of Western Ontario's journalism program in 1948 and immediately joined The Globe, staying until his retirement in 1990. Beginning in 1960, he was appointed literary editor and began a regimen of writing three columns a week devoted to reviews of new books as well as features and commentary about a young publishing scene in its heyday.

"He knew he had the best job at the paper," Paul French, one of three surviving children, said of his father. "It was all he ever wanted to do."

Reviews were enormously influential in determining a book's success in the last century, according to former Penguin Canada publisher Cynthia Good — and no critic was more influential than French. "His review was very important," she said. "It was the review of record."

Throughout his career French devoted special attention to new writers, being the first to introduce Canadian readers to such figures as Sandra Birdsell, Nino Ricci and Neil Bissoondath. Among the other writers who came to prominence on French's watch, often on his recommendation, were Margaret Laurence, Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Robertson Davies and Michael Ondaatje.

Receiving a nod from French could make a career, according to author Jane Urquhart. "He was a big presence in Toronto during the period I was growing up, so to have affirmation from someone who was already so distinguished was really important to me as a young author," she said.

In person, French was "an elegant, intelligent, charming, handsome guy," according to former Globe editor Edwin O'Dacre. "He was the go-to guy in criticism in Canada. He was the only legitimate voice. He was looked up to, and he had the presence that would allow you to look up to him."

Competitors at other newspapers were "just pale shadows" of William French, according to his colleague. "He was there at the time Canadian literature was burgeoning, and he was really on top of it all," O'Dacre said.

As much as he dominated the literary scene, French enjoyed a quiet life in suburban Toronto, living till his death in the same house he and his wife of 61 years, Jean Rollo, first bought in 1956. Over the years he constructed a series of what Paul French calls "fanciful bookshelves, with Scandinavian flair" to contain an ever-growing collection of books. "At last count there were 8,000 books in the house," Paul French said.

The sound of typing was constant in the house and the critic read everywhere, including the bathtub, according to his son. "He'd look at how wet the book got after reading and use that as an indication of how he felt about it."

French was the first Canadian to receive a fellowship from the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, and he and Jean spent 1954 in Cambridge with economist John Kenneth Galbraith and musician Dave Brubeck as neighbours — a "seminal experience" for the young couple, according to their son. French went on to teach courses at what is now Ryerson University, and he won two consecutive National Newspaper Awards in the 1970s for columns decrying censorship.

French's influence lives on in hundreds of "dust jacket blurbs," according to his son. But the most telling evidence of his impact on Canadian letters could be the fact that he was the last full-time book critic employed by The Globe.

"They retired his number," Paul French said.

The Globe and Mail - Monday July 30, 2012 - JOHN BARBER

Although his byline disappeared with his retirement more than 20 years ago, former Globe and Mail literary editor William French is still remembered by former colleagues and literary admirers as a giant of his day — Canada's dominant literary critic during a formative period of the national literature.

French, who died in Toronto last Tuesday at the age of 86, left the first graduating class of the University of Western Ontario's journalism program in 1948 and immediately joined The Globe, staying until his retirement in 1990. Beginning in 1960, he was appointed literary editor and began a regimen of writing three columns a week devoted to reviews of new books as well as features and commentary about a young publishing scene in its heyday.

"He knew he had the best job at the paper," Paul French, one of three surviving children, said of his father. "It was all he ever wanted to do."

Reviews were enormously influential in determining a book's success in the last century, according to former Penguin Canada publisher Cynthia Good — and no critic was more influential than French. "His review was very important," she said. "It was the review of record."

Throughout his career French devoted special attention to new writers, being the first to introduce Canadian readers to such figures as Sandra Birdsell, Nino Ricci and Neil Bissoondath. Among the other writers who came to prominence on French's watch, often on his recommendation, were Margaret Laurence, Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Robertson Davies and Michael Ondaatje.

Receiving a nod from French could make a career, according to author Jane Urquhart. "He was a big presence in Toronto during the period I was growing up, so to have affirmation from someone who was already so distinguished was really important to me as a young author," she said.

In person, French was "an elegant, intelligent, charming, handsome guy," according to former Globe editor Edwin O'Dacre. "He was the go-to guy in criticism in Canada. He was the only legitimate voice. He was looked up to, and he had the presence that would allow you to look up to him."

Competitors at other newspapers were "just pale shadows" of William French, according to his colleague. "He was there at the time Canadian literature was burgeoning, and he was really on top of it all," O'Dacre said.

As much as he dominated the literary scene, French enjoyed a quiet life in suburban Toronto, living till his death in the same house he and his wife of 61 years, Jean Rollo, first bought in 1956. Over the years he constructed a series of what Paul French calls "fanciful bookshelves, with Scandinavian flair" to contain an ever-growing collection of books. "At last count there were 8,000 books in the house," Paul French said.

The sound of typing was constant in the house and the critic read everywhere, including the bathtub, according to his son. "He'd look at how wet the book got after reading and use that as an indication of how he felt about it."

French was the first Canadian to receive a fellowship from the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University, and he and Jean spent 1954 in Cambridge with economist John Kenneth Galbraith and musician Dave Brubeck as neighbours — a "seminal experience" for the young couple, according to their son. French went on to teach courses at what is now Ryerson University, and he won two consecutive National Newspaper Awards in the 1970s for columns decrying censorship.

French's influence lives on in hundreds of "dust jacket blurbs," according to his son. But the most telling evidence of his impact on Canadian letters could be the fact that he was the last full-time book critic employed by The Globe.

"They retired his number," Paul French said.

The Globe and Mail - Monday July 30, 2012 - JOHN BARBER