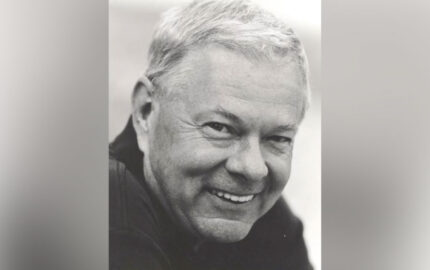

Robert Drew, NF ’55, whose 1960 documentary about John F. Kennedy, “Primary,” is regarded as the start of American cinéma vérité, died July 30 at his home in Sharon, Connecticut. He was 90. Drew, a former correspondent and editor at Life magazine, was instrumental in the development of the hand-held camera and synchronized sound recorder that enabled a team of two to make a film. Over a career that spanned five decades, Drew made more than 100 films on politics, social issues, and the arts. In a 2001 issue of Nieman Reports, Drew told the story of his career in “A Nieman Year Spent Pondering Storytelling”:

In the early 1950’s, with television in its infancy, the ability to capture real-life moments as they happen and use those images to tell a story was little more than an idea of what the documentary approach on this new medium might become. What had to evolve was an editorial approach that valued reality captured with the intimacy of the still camera and the technology to allow this to happen in motion pictures. But once that happened—and we knew it would—those of us wanting to pursue this new type of reporting would need to know how to transform these sounds and images into documentary television.

During my Nieman year in 1955, I focused on two questions: Why are documentaries so dull? What would it take for them to become gripping and exciting? Looking for answers, several Harvard mentors steered me towards an exploration of basic storytelling. So I studied the short story, modern stage play and novel, and watched how some of these forms came across on TV. TV documentaries were dull because they misused the medium. The kind of logic that builds interest and feeling on television is dramatic logic. Viewers become invested in the characters, and they watch as things happen and characters react and develop. As the power of the drama builds, viewers respond emotionally as well as intellectually.

What the prime-time documentary adds to the journalistic spectrum is the ability to let viewers experience the sense of being somewhere else, drawing them into dramatic developments in the lives of people caught up in stories of importance.

The right kind of documentary programming should raise more interest than it can satisfy, more questions than it should try to answer. When my Nieman year ended, it would take me five more years to conceive and develop the editing techniques, assemble the teams, reengineer the lightweight equipment, and find the right story to produce for my first TV documentary. “Primary” is the story of a young man who wanted to be president.

In the early 1950’s, with television in its infancy, the ability to capture real-life moments as they happen and use those images to tell a story was little more than an idea of what the documentary approach on this new medium might become. What had to evolve was an editorial approach that valued reality captured with the intimacy of the still camera and the technology to allow this to happen in motion pictures. But once that happened—and we knew it would—those of us wanting to pursue this new type of reporting would need to know how to transform these sounds and images into documentary television.

During my Nieman year in 1955, I focused on two questions: Why are documentaries so dull? What would it take for them to become gripping and exciting? Looking for answers, several Harvard mentors steered me towards an exploration of basic storytelling. So I studied the short story, modern stage play and novel, and watched how some of these forms came across on TV. TV documentaries were dull because they misused the medium. The kind of logic that builds interest and feeling on television is dramatic logic. Viewers become invested in the characters, and they watch as things happen and characters react and develop. As the power of the drama builds, viewers respond emotionally as well as intellectually.

What the prime-time documentary adds to the journalistic spectrum is the ability to let viewers experience the sense of being somewhere else, drawing them into dramatic developments in the lives of people caught up in stories of importance.

The right kind of documentary programming should raise more interest than it can satisfy, more questions than it should try to answer. When my Nieman year ended, it would take me five more years to conceive and develop the editing techniques, assemble the teams, reengineer the lightweight equipment, and find the right story to produce for my first TV documentary. “Primary” is the story of a young man who wanted to be president.