Photo courtesy of The Library of Congress.

One of the clearest memories of my youth is a conversation I had with my father in the summer of 1970. My dad had left his work in politics and the media to concentrate on the new phenomena of cable TV. (He would eventually go on to become the most successful cable consultant in Canada.) We were talking about why he wanted to switch careers when he said a most amazing thing. “Someday,” he told me, “you’ll be able to read your newspaper on the television.”

I looked at him like he had two heads. Read my newspaper on the TV? Oh sure, dad. And that’s what you’re going to base your new career on? I told him I thought he was crazy, that nobody would ever do something so weird.

My dad passed away 15 years ago, but often, as I read my newspaper, The Christian Science Monitor, on my WebTV, I’ve thought of my dad and wondered what he would think of the Internet and the new forms of journalism of the 21st century. Actually I know—he would love new media and all its possibilities. And I’d be lying if I didn’t say that this apple has fallen pretty close to the tree.

I’ve crossed my Rubicon as far as new media and journalism are concerned. Recently I thought about returning to print reporting after working in new media during the past eight years. But I realized that my definition of what it means to be a reporter had dramatically changed. In the past, my newspaper work meant finding a good story, doing interviews and research, and filing my stories or columns on time. Those elements remain at the core, but new elements have been added. Now I want to generate audio and video along with text. I want my email address on everything that I write. I want to participate in chats and forums. I want to use the new tools of modern storytelling available on a medium like the Web because they will add richness and depth to any piece on which I work. And I want to be able to get my pieces to readers as fast as possible, on whatever platform they want to receive it.

As we enter the 21st century, publishing digitally no longer just means putting up “shovel-ware” (or legacy content, as some call it) on a Web site. We face a future in which technology will change journalism, as it always has. Just as telephones gave reporters the ability to remain on the scene of a story longer or TV allowed us to tell news stories using moving pictures, these new media are already changing the way we do our jobs as journalists—whether we welcome those changes or not. While the basic tenets of journalism will remain the same (honesty, fairness, accuracy), almost everything else will change: how our work reaches our audiences/readers; the tools we use to do our jobs; the nature of the relationship we have with the people who access our work, and who are competitors are.

Welcome to the future of journalism. Please make sure your seatbelts are fastened, your chairs are in the upright position….

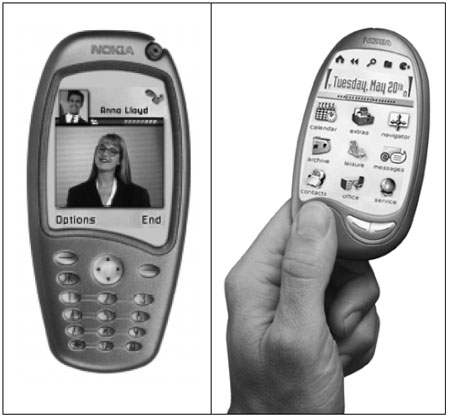

Nokia, a Finnish telecommunications firm, conceptualized terminals for its 3G (third generation) network. 3G is planned for test marketing in Japan in 2001 and in Europe in 2002. © Nokia, 2000.

Getting the News Out: How We Will Publish Content in The Future

There is a very important fact that all journalists must bear in mind—our future does not lie on the Web. In fact, if you believe some people, we should just forget about the Web altogether because its time as a distribution method is almost past.

That’s probably a little too pessimistic. The truth is, however, media outlets that focus only on the Web will be concentrating on too little, too late. That’s because the Web will be just one of many ways that we will get the news to those who want it. Other methods will include e-books, wireless cell phones, personal digital assistance (PDA) devices such as Palm Pilots, and probably several other methods we are not even aware of yet. Desire by the public for these methods of delivery, and the cost savings they will bring to the media who use them to publish, will drive these changes during the next decade.

The key to many of these changes will be improved screen resolution. Even though recent statistics from groups such as the Pew Research Center and The Poynter Institute show that more and more people are choosing to read their news online, few would say that it’s an experience they prefer to reading a newspaper or watching a TV. (Audio is an exception to this argument, as digital audio, via the Web or wireless, is already comparable to other media.) But at the recent Seybold Publishing Conference held in San Francisco, people who work in this area were saying that within two to three years, small devices like PDA’s or ebook readers will have screen resolution comparable to ink on paper. Only it will be better, they say, because it will be back lit (so you can still read in the dark), with better contrast. Larger screen technology is about five years away.

When these better screens become available, it will have an enormous impact on the delivery of new media content. The old saw of “You can’t read it on a bus or take it into the can” will mean nothing, because hand-sized reading devices will enable you to read/watch/hear media content any place you like. And as these reading devices drop in price, you’ll see many publishers start offering deals where customers will buy/rent a reading device from them. You’ll still be able to access other content (probably via subscription) but the devices’ default setting will all be set to the primary publisher. (AOL and Microsoft are already marketing tablet sized devices that include wireless Internet access.)

And speaking of wireless, it will become the primary platform on which to publish digital content. Currently Sprint PCS, for instance, offers wireless access to the Internet, but it’s mostly text and made for very small screens. Sprint, however, has started marketing wireless phones with much bigger screen areas and plans to have broadband access available on phones within two to three years. Imagine broadband access in the palm of your hand—which includes rich graphic and video capabilities. You will literally be able to watch any TV station in the world if it has an Internet output (as most radio stations do today).

None of this is science fiction—it’s all currently available or in a testing mode and will be available within the next few years.

Give Us the Tools and We’ll Finish the Job

A couple of weeks ago, during one of those beautiful fall New England days that seem to sneak past winter’s guard dogs just before he decides to clobber us, I sat in Copley Square and wrote a column on my laptop. I didn’t dictate it into my voice recognition software (which is how I normally “write” my first drafts—this piece, for instance, was about half typed, half spoken), because the background noise was a little loud. When I finished, I took my wireless phone out of my pocket, connected it to my laptop, got a good 56 kbps connection, and e-mailed the story back to the Monitor. Then I used my Instant Messaging software to chat with the editor of the piece about how he planned to edit it. (My mother-in-law, who lives in Turkey, saw I was online and “chatted” with me as well.)

Also this fall I attended a conference called “Being Human in the Digital Age,” in Camden, Maine. I used my digital voice recorder to “tape” an interview with James Adams, the head of an Internet security firm called iDEFENSE. That night, I downloaded the digital audio to my laptop and sent a copy of the entire interview back to the Monitor so our audio people could do some editing. I also sent back a few digital photos I had taken. I would have had sent video but I had forgotten to bring that camera.

Technology is quickly eliminating the usual reasons reporters find to avoid creating extra material for their new media partners. For instance, the digital audio recorder is only slightly larger than a cigarette lighter. The video camera is palm-sized. Laptops are shrinking and soon will be half the size and weight they were only two years ago. In other words, the barrier to creating more content has more to do with attitude than with inconvenience. This is particularly true for print reporters, who love to complain about how overworked they are. (I was a print reporter for a long time—I remember the drill.) And while they are overworked, the reality is that most of the extra content mentioned above took almost no extra time to create or prepare.

And as much as some reporters may hate to hear this, creating this extra material will soon become a part of every reporter’s job description. That doesn’t mean the act of storytelling, which comprises the heart of good journalism, will change. But the tools we will use will definitely change.

Let me offer an example of a technology that most reporters will be eager to use. Currently, voice recognition software only allows the person who “trains” the software (to recognize their voice) to create a text file from an audio recording. But Lernout and Hauspie of Burlington, Massachusetts, one of the leading voice recognition companies, say they are about two years away from having a system where you can tape anyone you like, and it will transcribe all voices, no voice training needed. No more madly scribbling notes during interviews. Just tape it, download it, and transcribe it with the proper software.

Let Freedom Ring: the Impact Technology is Having On Journalism Around the World

As journalists in North America argue about whether or not we want to receive e-mail, the Internet and technology are changing the face of journalism around much of the world. (I am indebted to Adam Powell of The Freedom Forum for examples mentioned below.)

E-mail in particular is transforming newsgathering. For instance, 10 years ago The Johannesburg Star in South Africa covered the neighboring countries of Africa using the wires like The Associated Press or Agence France-Presse. But in recent years, as editors and reporters around Africa started getting e-mail, the Star has been able to generate its own coverage of sub-Saharan Africa. As one editor recently told Powell, African journalists are now constructing their own journalism, and they are no longer dependent on an American or European view of what is happening on their own continent. And now, these same news outlets are beginning to share digital video and audio feeds.

Another great example of how technology is changing modern journalism is transpiring among Arab publications in the Middle East and Northern Africa. A group of editors set up a password-protected Web site in London where Arab editors can file an uncensored version of stories they run in their publications. The idea is that other editors around the Arab world can read these stories, and although they can’t run them, it allows them to know what’s really happening in other Arab countries so they can shape their own coverage to reflect the truth. Perhaps an even more interesting comment came from one Arab editor who told Powell that the Internet is finally allowing his paper to cover America in depth. When Powell asked what that meant—after all, the Arab countries all get CNN and such—he replied that he had been able to create a network of Arab correspondents in the United States who cover events in the United States from an Arab perspective.

Within a few years, it will be impossible for authorities in totalitarian or communist countries to prevent their citizens from having firsthand knowledge of the news. Meanwhile, countries long accustomed to an American view of the world are finding ways to create news as viewed through their own filters.

Turning a Buck—a Thousand Revenue Streams of Light

Journalists who hate the Internet and all it stands for are fond of saying that while new media might have all the sizzle, old media has all the steak. And it is true that most new media companies are either losing money or just breaking even.

The problem of revenue for new media was that for a long time we were trying to pour old wine into new bottles. The models we had for revenue generation all came from older media. But it’s becoming increasingly clear to those of us who work in new media that there is no one single river of revenue (like display ads or classifieds in newspapers), but many small streams that come together to create a larger river.

Banner ads will generate some revenue, but it will never be the magic bullet envisioned in the beginning of new media. Newer revenue streams include selling access to archives, new syndication deals in which Web sites sell their content to companies like Screaming Media and iSyndicate—who then sell it to other Web sites or for use on a company’s intranet—and the creation of personalized editions. (All of these methods generate revenue for us at the Monitor.) And once micro-transactions are available in about a year or so, permitting media companies to sell content for pennies, rather than dollars, fee-based models will be much more acceptable to readers/users.

But here’s something we’ve also discovered at the Monitor. The Monitor’s Web site, csmonitor.com, has become one of the main ways for people to subscribe to our print edition. In fact, we sell almost as many subscriptions online as we do via direct mail or other advertising methods. And the retention rate of people who sign up via the Web site is twice as high as for those who sign up through other methods. I believe this is because people use one medium to complement the other. In other words, they like having a choice. In the future, new media outlets that work hand in hand with old media counterparts will be the ones that prosper. That’s because the secret to making money with new media is for media companies to see themselves as content providers, and not just newspapers, radio stations, etc.

And here’s the other bottom line about revenue. It’s a hell of a lot cheaper to get the news to people via digital methods than analog ones. Ultimately this fact alone will convince many media outlets to switch to new media models.

And in Closing…

A few years ago I attended a conference held by the Nieman Foundation on journalism and technology. The two-day conference turned into an Eyesore wail of how new media were going to ruin journalism. During one particular gloomy panel about the future of journalism, a man standing beside me leaned over and said, “It’s like listening to a group of 15th century monks talk about the printing press.”

I will never forget his words because he spoke the truth. People hate change and journalists hate it more than most people. We are a skeptical group by nature and view all change through a jaundiced eye. After all, that is what we are paid to do for most of our professional lives. So it’s easy to understand why some journalists are fearful and suspicious of these changes.

Without sounding too much like a fatalist, it’s important that we realize that most of the changes described above are inevitable. But the reality is that the elements that make good journalism, and good journalists, will never change. Ignoring the future doesn’t mean we can escape it. But paying attention to it means we can shape it. There are many battles still to be fought on the digital battlefield—like privacy, access to information, and access for all to these new media. Good journalists will be needed to report on these topics, as well as all the other issues that people are talking about.

In the end, it’s all about our readers/ viewers/audience and getting them reliable information in a timely manner. If we focus more on their needs, and less on our complaints, then moving into the new media era will be a piece of cake.

Tom Regan, a 1992 Nieman Fellow, is associate editor of The Christian Science Monitor’s Web site at www.csmonitor.com.