It’s been six years since renowned Peruvian journalist Gustavo Gorriti wrote “Fake news is nothing new. What is rather exceptional is good journalism.” Those lines, penned in his column “The Words,” published in the Latin American edition of El País, still ring true.

In his 2018 article “Fake News with a Past,” Gorriti argued that the decisive events of the 20th century were fought under the shadow of propaganda and disinformation, emphasizing the significance of that perspective amid the rise of populist leaders and fake news superspreaders like Donald Trump.

Fast forward to today and populist leaders like Trump are no longer a novelty and fake news continues to plague our societies. But robust investigative journalism in Latin America is now a reality. This is largely thanks to the work of journalists like Gorriti.

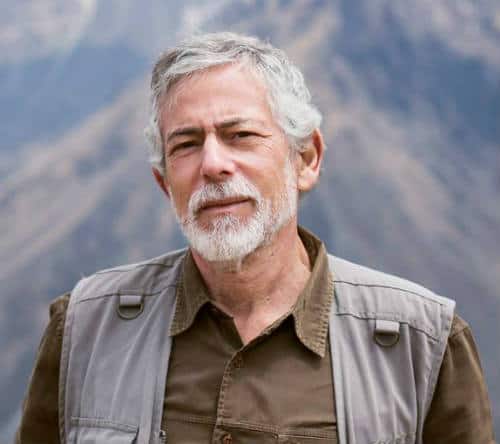

Throughout his career, Gorriti, a 1986 Nieman Fellow and founder of the investigative journalism outlet IDL-Reporteros, has mentored countless journalists. Millions of readers in Peru and across the region have learned about corruption among the powerful from his reporting. His famous Lava Jato investigation is just one case in point. However, Gorriti, now 75, not only battles against aggressive cancer but also the legal threats of those he once investigated who seek to imprison and silence him. They are sending a message: If they can target him, what will they do to those who do not have his influence and prestige?

A decade ago, Gorriti led IDL-Reporteros’ investigation of the Lava Jato case, considered the biggest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history — and probably in Latin America. The probe followed the trail of payoffs made by the powerful Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, exposing widespread bribes made to politicians, businessmen and officials across the continent. In Peru, the impact was particularly severe with Odebrecht financing four presidents and the leading opposition figure, Keiko Fujimori, all of whom faced legal consequences, including imprisonment or house arrest.

Now, the Prosecutor’s Office is investigating Gorriti for allegedly promoting the image of the two special prosecutors of the Lava Jato case in Peru in exchange for information. Consequently, the Prosecutor’s Office is pressuring Gorriti to disclose his sources and surrender the phones he used between 2016 and 2011.

The persecution of Gorriti has sparked a wave of solidarity among journalists, exemplified by a letter of supportorganized by journalist Kathy Kiely during the recent ISOJ conference run by1988 Nieman Fellow by Rosental Alves. The letter is still open for signatures. This solidarity is urgently needed as the persecution of journalists in Latin America persists.

Gorriti’s case is only the most recent in a worrying series. In Guatemala, another symbol of journalistic integrity, José Ruben Zamora, founder of elPeriódico, has been imprisoned since July 2022. Zamora faces money laundering charges, vehemently contested by him. His arrest followed the paper’s exposure of alleged corruption in former president Alejandro Giammattei’s administration. Although Zamora was sentenced to six years, an appeals court overturned the conviction last October and ordered a new trial. However, elPeriódico, a venerable institution in Guatemala, was forced to cease operations in May 2023.

The list of persecuted journalists in the region seems endless. Carlos Fernando Chamorro, an iconic Nicaraguan journalist, is the most visible face of the hundreds of journalists from the country who work in exile because of the oppression of the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo regime. In El Salvador, Carlos Dada and the reporters of El Faro face similar persecution. El Faro had to move its operations to Costa Rica due to the continuous attacks by President Nayib Bukele. Today, the focus is on Peru, Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador but Venezuelan journalists are still fighting for safety and freedom. Not long ago, Colombian journalists were in the same situation. And let’s not forget the brave reporters from Mexico, navigating one of most dangerous countries for journalists outside of a war zone.

Discussing journalism in Latin America means talking about threats, exile and even assassinations. It also entails a more insidious form of violence — the systematic attack on checks and balances from the powers that be. These assaults seek to sow more and more doubts about the integrity and credibility of journalists, as we can see with Gustavo Gorriti.

“The positive aspect of Trump is that he is loud enough to worry us,” Gorriti wrote in his column in El País America six years ago. We all worry about what Trump might do if he returns to the White House, but we should also be concerned about the less publicized persecutions of journalists that are replicated increasingly around the world.

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to participate in the Tuesday seminar organized by Professor Steven Levitsky at Harvard’s Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. I called my talk “Journalism in Latin America: Reporting in Minefields” because I believe that journalism in the region does not stop despite the constant threats it faces. You never know when a mine might explode beneath you. The mine is a metaphor for the attacks from the political and economic elite and organized crime. There is no way to do serious journalism in Latin America without navigating a minefield.

The idea of the mine also has a separate metaphorical component that is not related to anti-personnel mines, but rather to caves. Miners used to bring along canaries when they entered a cave because they could detect toxic gases before humans. If the bird stopped singing, everyone would run out. The canary in a coal mine. I think that we journalists can be those birds. The miners are society and democracy. The day journalists stop singing, democracy will be in danger. Both generally speaking and according to the data, I believe that Latin America is more democratic than it has been in recent history. And I also believe that the moment that journalism is experiencing now is warning of a democratic backslide in the region. We must listen to the canaries who are alerting the miners.

Javier Lafuente, a 2024 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, is deputy managing editor of the American edition of the Spanish newspaper El País and is based in Mexico City.