This is an edited version of a talk given on April 7, 1941, to the Nieman Fellows by Harry J. Grant, a long-time associate of Mr. Nieman and his successor in publishing The Milwaukee Journal.

It is difficult to interpret the workings of another man’s mind and to analyze his motives clearly. Sixty years of Mr. Nieman’s life — 35 of them with The Milwaukee Journal — had passed when I first met him. He impressed me by his straight thinking and his genius in digging out facts. He possessed great charm and the hardships which had come his way helped to give force to his character and effectiveness to his work.

Early in life he decided to be a newspaperman and for more than 60 years he followed his idea to the end of a most successful career.

Child of Pioneers

“Lute” Nieman, as he was intimately called, was born in Bear Creek, Sauk County, Wisc., Dec. 13, 1857. He died in Milwaukee on Oct. 1, 1935. Child of pioneer parents in pioneer country, his methods through life remained those of the pioneer. Away from beaten paths, he went alone, frequently lonely but always bravely, true to his principles, with an instinct of the hazard in all new movements and a caution that demanded factual assurance.

His father, Conrad Nieman, was the child of early farmers in this undeveloped country, as was his mother, Sara Elizabeth Delamater. Lute and his elder sister Violette were the only children.

Grandfather Delamater was of French pioneer stock; and his wife, Susan Cuppernall, had come with her family from Oneida County, New York. When Lute was 2 years old, his father died and his mother took the two small children to live with her parents near Mukwonago.

After a few years the mother died, and Lute was cared for by Grandmother Delamater, who accepted the responsibility of his early training. He received the usual grade-school education of the period and discussed the news of the day with the family and the schoolteacher who boarded with them.

The influence of this small group was indelibly marked on Lute’s future life, and it was in this village of 1,000 persons, 25 miles southwest of Milwaukee, that he first came in touch with events of the outside world. He was fascinated by them and formed his boyhood resolution to be a newspaperman.

Working at the Age of 12

In response to his constant pleas to become an editor, Grandmother Delamater called upon the friendly assistance of the former schoolteacher, Theron Haight, then editor of The Waukesha Freeman.

At the age of 12, Lute became a printers’ devil on that weekly newspaper. He ran errands, folded papers and willingly did whatever he was told to do, finally learning to set and distribute type.

He boarded at the home of Mr. Haight, and his active world was that of the country newspaper. He had never been away from home, and on weekends he visited Grandmother Delamater at Mukwonago. At times of bitter homesickness he received encouragement and inspiration from her.

Two years later, in 1871, he went to work in the composing room of The Milwaukee Sentinel. He enjoyed his work and took pride in becoming an expert. The president of The Sentinel Company advised him to get into the “writing end” of the business. With this in mind, Mr. Nieman spent the following winter at Carroll College in Waukesha, residing with his Grandmother Delamater who then lived there.

No Compromise

Here he first became an editor when he served as Waukesha correspondent for The Sentinel. Later he returned to Milwaukee to become a reporter for that paper and act as its correspondent in Madison, the state capital, during the year 1875. He was managing editor of The Sentinel from 1876 to 1880, and his grasp of the important events of the day and the true values of the news made him, at 21 years of age, the successful executive of the then-largest newspaper in Wisconsin.

He had become a newspaperman and did his best to collect, edit and print the news fully and truthfully. There were no side issues, no secret concessions or compromise of any sort; and this was the cornerstone of his success because newspapers at that time were largely political organs or toys in the hands of wealthy men with outside interests to which their newspapers were subservient.

It is not difficult to understand Mr. Nieman’s desire to become the owner of his own newspaper. In casting about for such an opportunity, he went to St. Paul as managing editor of the St. Paul Dispatch, then owned by Governor Marshall of Minnesota. Here he acquired a third interest with the offer of majority stock if he could restore the property to leadership and profit. He accomplished the task within a year but relinquished his interest because he was homesick for Milwaukee.

Plans for a New Paper

About this time James C. Scripps of Detroit discussed backing Mr. Nieman in the establishment of a new Milwaukee paper, though there were already several. But Mr. Scripps lost interest when a new newspaper, The Daily Journal, was started as a campaign sheet by P. D. Deuster, a candidate for Congress.

Mr. Nieman saw his opportunity in this event, and on Dec. 11, 1882 — 22 days after The Daily Journal had been started — he purchased a half interest and later a majority interest. The boy who wanted to be a newspaperman was now, at 25, the controlling owner and executive head of his own newspaper.

The beginning was small, indeed — a single sheet, both sides printed on a flat-bed press, folded to make four pages of five columns each, the columns being lengthened whenever the news volume required it. Seldom was there even a wood-cut illustration in the early issues. The circulation price was 2 cents; its competitors sold for 5 cents. This differential was to play an important part in the paper’s future growth.

The presses were leased from a local German daily newspaper, as was the limited space for a composing room. The paper’s entire business was handled from one desk with 100 square feet of office space. The chief responsibility fell to Mr. Nieman. He was publisher, editor and circulation manager; he served as typesetter, a tedious job, when the extra load was too great for the small force.

Without Fear or Bias

For half a century The Journal was guided by Mr. Nieman, a record seldom equalled in American journalism. Yet it was never a one-man paper in the sense of being influenced by petty personal whims. It has never been a party-controlled paper. It has valued its freedom above everything else.

It has followed Mr. Nieman’s code to make a newspaper without fear and without bias in its news columns. Its editorial opinions have been soundly based on the facts within the news. It has believed in the ability of the public to judge it correctly.

Though resources were small, the first Journals revealed a completeness and care in editing and preparation that commanded attention. Spurred on by necessity, at times desperately in need of funds, accepting hardship as part of growth and development — so did Lucius William Nieman come by a better understanding of and confidence in himself, which was not easily shaken.

Careful Editing

In newspapers of those days, telegraph news was usually given importance far beyond its worth because of its cost and extra wire tolls. Mr. Nieman edited such news carefully and stopped the practice of padding ordinary stories. His objective was to get and print the news as it occurred, rather than as he might have wanted it.

Under Mr. Nieman’s guidance, The Journal stood squarely on the side of the people instead of any class in all questions involving political rights, economic welfare and social justice. This was done as a matter of principle and also in the firm belief that it would safeguard our institutions to make government truly serve the public welfare.

In this phase of its career, The Journal was a crusading newspaper — not from design, but because Mr. Nieman held fast to his idea of freedom and accuracy in printing the news.

Some two months after Mr. Nieman bought The Journal, Milwaukee’s leading hotel, the Newhall House, burned to the ground, causing the death of more than 70 guests. It proved to be a firetrap, though advertised as fireproof. Efforts were made to hush the scandal that ensued, but The Journal rewarded its readers’ confidence by printing the story in full.

Free from Political Influence

Mr. Nieman believed that the city’s educational program should be free from legislative influence and restrictions, as he had always fought to keep the courts free from political control. For this reason he opposed the Bennett law, which made the teaching of foreign languages illegal in the grade and parochial schools of the city.

It had been the practice of Wisconsin state treasurers to credit to their own account the interest on state bank balances, and from 1893 to 1900 The Journal conducted a campaign to force them to comply with the law and refund such moneys. More than half a million dollars was restored to the state treasury by this work.

When in 1888 The Journal supported Grover Cleveland for president, its financial life was threatened because of moneys which it owed to the backers of another candidate. Again in 1896, when bolting William Jennings Bryan on the silver issue, it lost temporarily one-third of its circulation.

One thing that was never lost was Mr. Nieman’s courage to follow his own convictions. He was always broadly independent in his political views and did not hesitate to defend them.

“Not To Do Injustice To Anyone”

The Journal led the successful fight to eliminate national party labels from municipal-election ballots and to elect city officers by a majority vote. The Journal took a strong position in favor of such democratic measures as the election of U.S. senators, and even a president, by direct popular vote. It fought long and strenuously for municipal home-rule: the right of cities to formulate their own local policies and to manage their own affairs.

On the 50th anniversary of The Journal, Mr. Nieman said “there was no partisanship in the editorial direction of The Journal. It set out to print the news; its policies were based on sound economic principles regardless of political, financial or other considerations. . . .

“In its news stories it has kept up unceasingly the effort not to do injustice to any one or bring into its stories what might hurt people innocent of all offense. This we do not think of as something particularly virtuous but simply as trying to be square — a policy which makes a newspaper trusted and wins it a place in the life of its community.”

So spoke Mr. Nieman, clearly and to the point, as usual devoid of all pretense, always seeking the facts as a basis for printing the news. Many, many times he would ask: “Whom does he represent? Is there a call for this or that? Is the thing real or artificial? What results can be expected, given this or that turn of events?” His was a direct and homely approach, showing a sympathetic interest in all classes of people.

Pulitzer for Public Service

In 1919, the Pulitzer Prize was awarded The Journal for the “most disinterested and meritorious service rendered by any American newspaper during the year.” This reward came as a result of Mr. Nieman’s keen understanding of issues at a time when various racial groups endeavored to use this country in behalf of their own homelands.

To dig out the material being used as propaganda by foreign governments, it was necessary to translate nearly five million words. The Journal carried on this work so that the facts might be kept straight.

Mr. Nieman stated that he did not consider The Journal’s activity as anything particularly courageous beyond trying to print the news fairly as an American newspaper. He called it “a great responsibility, but a greater opportunity… the opportunity to speak up for the birthright of Americans, the dearest thing that anyone of us can possess… As the voice of a community and a commonwealth our duty was plain… No thought of courage came to us… We had but the alternative of sinking into contempt.”

Best Friends

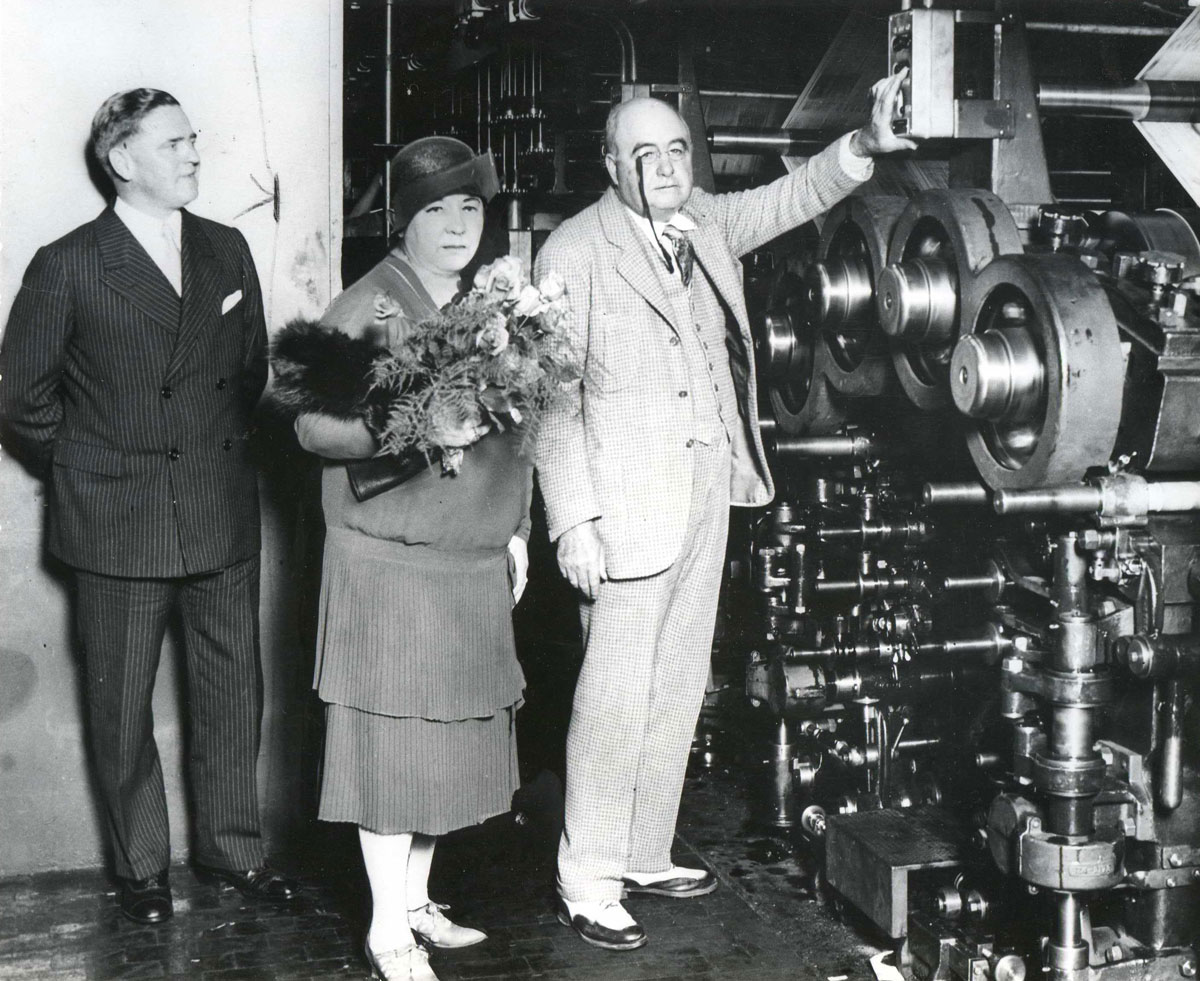

On November 29, 1900, he married Agnes Elizabeth Guenther Wahl, a leader in Milwaukee’s social and intellectual life. She was the daughter of the late Christian Wahl, one of Milwaukee’s most public-spirited citizens who, as a result of his efforts to serve the public personally as well as publicly, became known as “the father of Milwaukee’s public park system.”

Mrs. Nieman was Lute’s best friend and almost constant companion, as well as a devoted wife. Their many mutual interests made for a genuine and happy household.

She was to live less than six months after he passed away and was to create a fund in his memory for the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University “to promote and elevate the standards of journalism in the United States and educate persons deemed especially qualified for journalism.”