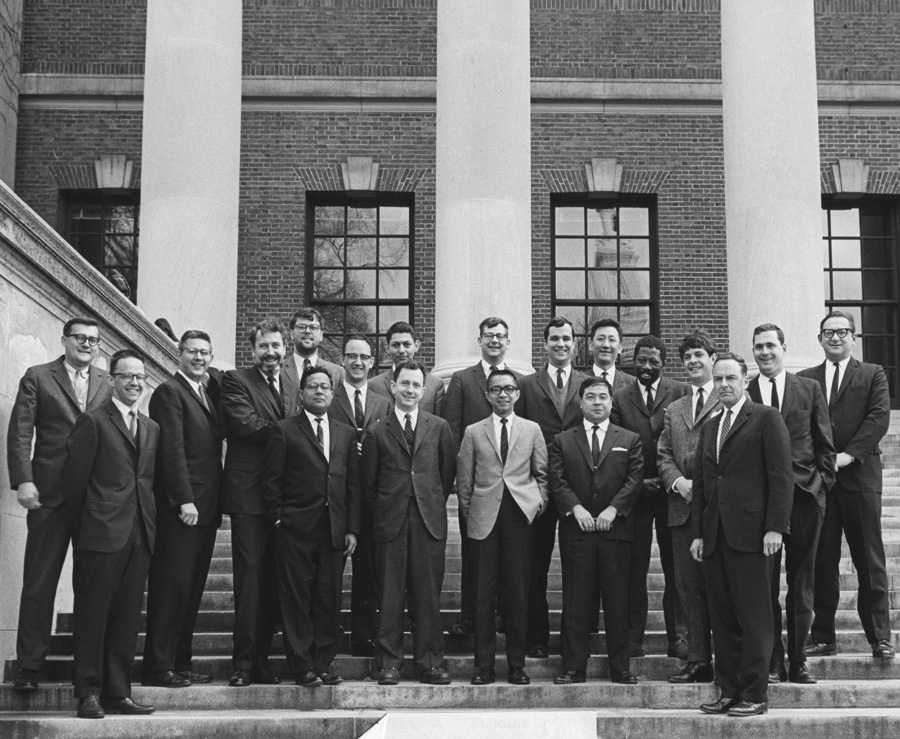

When news came of Ralph Hancox’s passing, my instinct was to find an old photograph of the Nieman Fellows’ class of 1966. There he was in the first row, towering over the rest of us clustered on the steps of Widener Library.

Ralph was Lincolnesque; tall, lean with a mop of dark hair and a thick beard that was not common among journalists of the day. In the instant captured in the photograph, his face was wreathed in a broad grin, as if he had said something funny, which he often did.

His demeanor—and that of his wife, Peg, and their four children—reflected the influence of their British and Canadian roots: polite, thoughtful, well mannered. Ralph was one of six international fellows that year in a class of 19 and he tolerated with good grace the teasing about being from Canada.

Ralph came to Harvard from the Peterborough Examiner in Ontario where he had learned what it took to be a small-town editor. During the year, it was announced that he had won the National Newspaper Award for editorial writing. His deep sense of modesty restrained him from saying much about that prize or about some of his other notable experiences: training for the Royal Air Force in Rhodesia and then flying in the Berlin Airlift in 1948. It wasn’t until years later that he revealed his role in a risky adventure on a secret mission under the Wall from East to West Berlin in 1961.

Ralph was not your typical Nieman Fellow. W. Hodding Carter III, also a member of the class of 1966, remembers that he “did not come out of our playbook: no university, no minute fascination with U.S. politics, no tolerance for ideologues of any sort. He had a deep and informed appreciation of the arts. I don’t think we fully appreciated how lucky we were to have his leaven in our lump of fairly conventional dough.”

Ralph was Lincolnesque; tall, lean with a mop of dark hair and a thick beard that was not common among journalists of the day. In the instant captured in the photograph, his face was wreathed in a broad grin, as if he had said something funny, which he often did.

His demeanor—and that of his wife, Peg, and their four children—reflected the influence of their British and Canadian roots: polite, thoughtful, well mannered. Ralph was one of six international fellows that year in a class of 19 and he tolerated with good grace the teasing about being from Canada.

Ralph came to Harvard from the Peterborough Examiner in Ontario where he had learned what it took to be a small-town editor. During the year, it was announced that he had won the National Newspaper Award for editorial writing. His deep sense of modesty restrained him from saying much about that prize or about some of his other notable experiences: training for the Royal Air Force in Rhodesia and then flying in the Berlin Airlift in 1948. It wasn’t until years later that he revealed his role in a risky adventure on a secret mission under the Wall from East to West Berlin in 1961.

Ralph was not your typical Nieman Fellow. W. Hodding Carter III, also a member of the class of 1966, remembers that he “did not come out of our playbook: no university, no minute fascination with U.S. politics, no tolerance for ideologues of any sort. He had a deep and informed appreciation of the arts. I don’t think we fully appreciated how lucky we were to have his leaven in our lump of fairly conventional dough.”