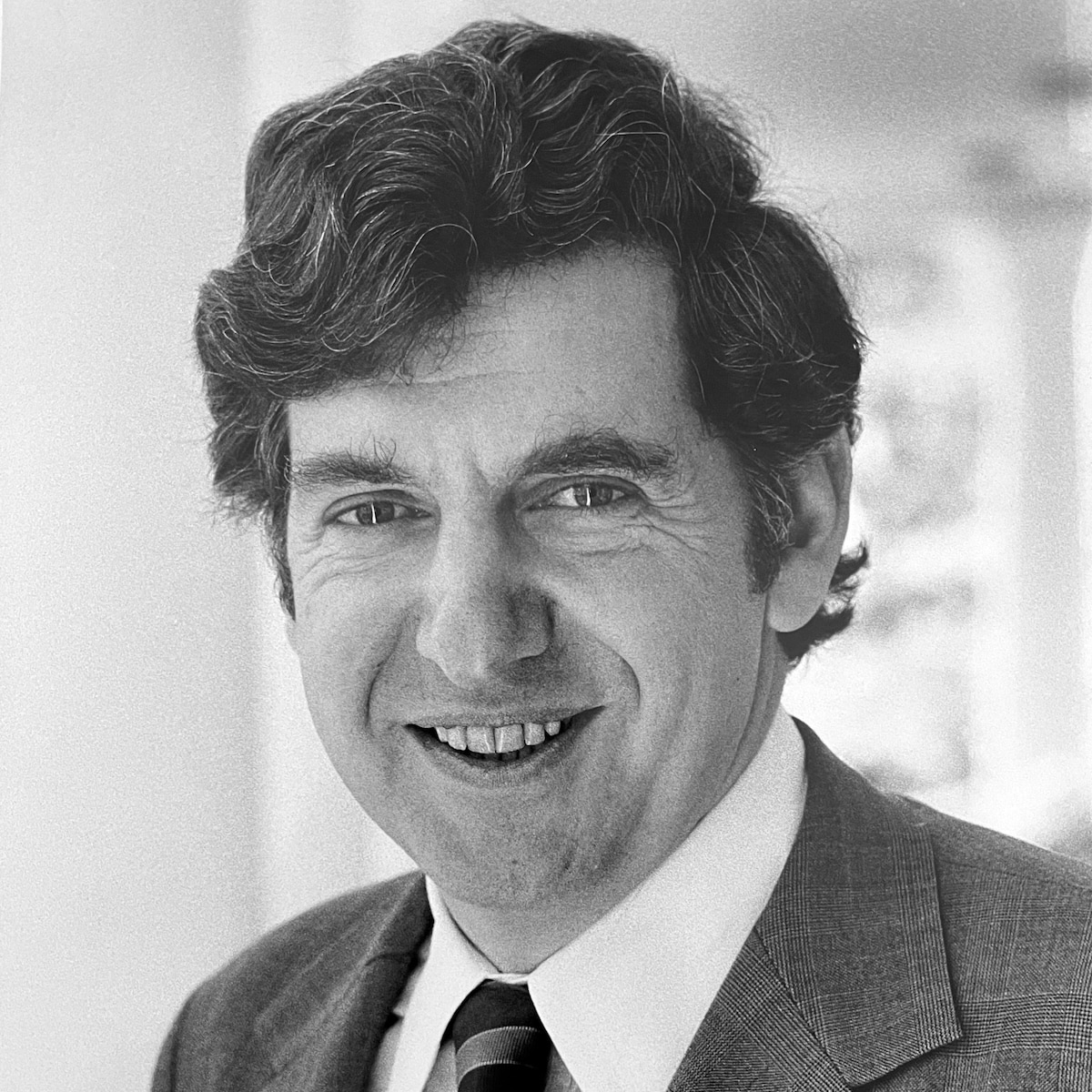

Jerrold L. Schecter, a 1964 Nieman Fellow who reported from Asia, the Soviet Union and the White House for Time magazine and wrote for several other publications, died at his home in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 6, 2023, at age 90.

Born in 1932 in New York City, he graduated from high school in the Bronx and earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he worked on the school newspaper with his future wife, Leona Protas. After graduating, he served in the Navy in Japan and Korea.

Early in his journalism career, Schecter worked briefly for The Wall Street Journal as a staff correspondent before joining Time magazine in 1958. There, he served as contributing editor and then a staff correspondent covering China, Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. After his Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University in 1963-64, he served as the Time-Life bureau chief in Tokyo, before becoming Time’s bureau chief in Moscow and later Time’s White House correspondent and diplomatic editor. He also worked as Washington editor and foreign affairs columnist for Esquire in the 1980s.

Schecter notably helped in the publication of “Khrushchev Remembers,” which first appeared in Life magazine and as a Little, Brown book in 1970. Based on a series of audio tapes recorded by former Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev after he was ousted from power, it was the first account by a Soviet leader to reveal the inner workings of the Kremlin.

As Schecter recalled in Nieman Reports: “As Time magazine’s Moscow bureau chief, I was instrumental in acquiring and secretly validating the authenticity of Khrushchev’s terrifying revelations of how Stalin’s excesses led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. As a journalist, I struggled to confirm the authenticity of the tapes. Time had them all voice-printed to confirm that they matched Khrushchev’s voice at a United Nations speech in New York City…What I took away from the memoirs, which turned into a total of three volumes, was that Khrushchev played an instrumental role in destroying Soviet communism with his revelations, which he intended to salvage and restore his own place in history.”

In the late 1970s, he served as associate White House press secretary and spokesman for the National Security Council under President Jimmy Carter.

In the early 1980s, he was vice president for public affairs at Occidental Petroleum Company.

Schecter stood by assertions made in his book “Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness — a Soviet Spymaster” (Little, Brown, 1994) — written with KGB officer Pavel Sudoplatov, his son Anatoli Sudoplatov and Leona Schecter— that nuclear scientists had shared information with the Soviets. Both the FBI and the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service denied the validity of the claims.

Schecter’s other books include:

- “The New Face of Buddha: Buddhism and Political Power in Southeast Asia” (Coward-McCann, 1967

- “An American Family in Moscow,” (Little, Brown, 1975) and “Back in the U.S.S.R.: An American Family Returns to Moscow” (Scribner, 1988), both written with his wife Leona Schecter and their children. The accompanying documentary television special “Back in the U.S.S.R.” was produced by PBS in 1988.

- “The Palace File: The Remarkable Story of the Secret Letters from Nixon and Ford to the President of South Vietnam and the American Promises that Were Never Kept” (Harper & Row, 1986), co-written with Nguyen Tien Hung and named by The New York Times as one of the best books of the year in 1987

- “Khrushchev Remembers the Glasnost Tapes” (Little, Brown, 1990) Schecter was editor and translator.

- “The Spy Who Saved the World: How a Soviet Colonel Changed the Course of the Cold War” (Scribner, 1992), co-authored with Peter Deriabin

- “Russian Negotiating Behavior: Continuity and Transition, U.S. Institute of Peace Press” (United States Institute of Peace, 1998)

- “Sacred Secrets: How Soviet Intelligence Operations Changed American History” (Brassey’s, 2002), co-authored with Leona Schecter

He leaves his wife Leona Schecter, their five children, Evelind Schecter, Steven Schecter, Kate Schecter, Doveen Schecter and Barnet Schecter, 10 grandchildren and three great-granddaughters.

Memorial contributions may be made to the Committee to Protect Journalists.