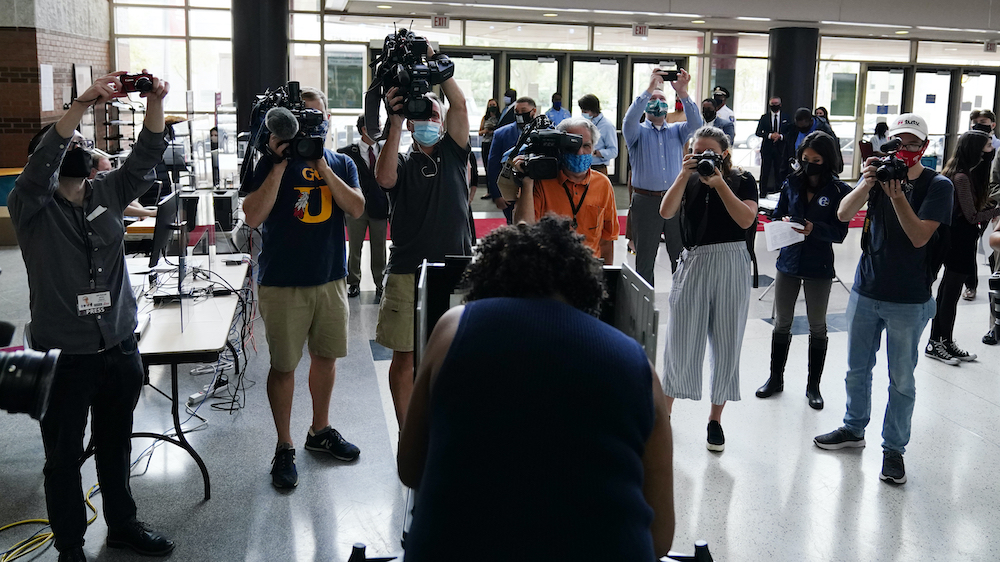

News media photograph Philadelphia resident Priscilla Bennett as she fills out her ballot at the opening of a satellite election office at Temple University's Liacouras Center at the end of September 2020

It’s the electoral climax Americans have grown accustomed to over the course of decades: That dramatic moment when the TV anchor announces his or her network can “call” the winner of the election to be the president of the United States.

It has never really meant what it seems. Votes keep getting counted for days, and the results aren’t officially certified for weeks. But in a society eager for ever-more instant gratification, the sophisticated statistical modeling that allowed news organizations’ “decision desks” to declare a victor helped turn America’s grandest democratic exercise into an equally American made-for-TV moment. Now it’s a big deal if you have to go to sleep without knowing the next president.

In 2020, we might also wake up without a winner, go to sleep again without a winner, and over and over for a few days of purgatory. Journalists need to be ready for that — and we need to prepare our audiences for the same.

The huge expansion of mail voting during a once-a-century pandemic has made the politics story of 2020 as much about the mechanics of running an election as it is about Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Nowhere is that more true than in Pennsylvania. Here, universal mail voting was enacted before the pandemic and was expected to ramp up slowly. Yet more than half of voters did so in the June primary, and mail ballot requests have again surged for the general election.

But Pennsylvania is one of only a few states facing a deluge in mail ballots where election officials are also legally prohibited from beginning to count until the polls open on Election Day — raising the possibility of a days-long process to tally them all. In Philadelphia, counting dragged on for weeks after the primary.

Then there’s the added complicating factor of President Trump. His false but relentless attacks on mail ballots as being susceptible to widespread fraud have taken what was a nonpartisan issue — voting by mail — and made it a deeply partisan one. Democrats are requesting mail ballots at hugely disproportionate rates compared to Republicans. Take Democrats casting votes that are slower to count, add Republicans casting votes that are faster to count, mix in a president who has eagerly undermined confidence in the electoral system — and you’ve got a recipe for the chaos of a premature claim of victory.

Add in the fact that Pennsylvania’s 20 Electoral College votes could determine the winner, and you’ve also got a national spotlight.

At The Philadelphia Inquirer, we’re preparing for the challenge of covering this possibility and many others. The operative words are calm and context. We won’t be in any rush to say there’s a winner, regardless of whether candidates, their supporters, and even our readers are. If the preliminary results available that night reflect mostly or only the in-person votes cast on machines, we’ll ensure our readers know not only that, but also what that means. And if the slow counting of mail ballots in the days after happens to turn a Trump lead into a Biden win, we’ll make clear in unambiguous language that it’s not fraud, it’s not the election being stolen — it’s just the votes being counted, albeit slowly. It’s the system working.

But the work starts long before Election Day. The most important part is the basic work of voter education — preparing voters for what to expect. Our singularly talented voting reporter Jonathan Lai has been covering the possibility of a days-long count since even before the pandemic, as well as the likelihood of what’s known in academic circles as a “blue shift” as mail ballots are slowly counted.

Key to that work is speaking plain truths in every story, without equivocation or unnecessary qualification. Trump’s attacks on mail voting are not offered “without evidence.” They are not “disputed by experts.” They are false. Full stop.

The stakes are particularly high here. “Bad things happen in Philadelphia,” Trump said during a debate last month. From the president’s rhetoric on national TV to his campaign’s lawsuit against the city over poll watchers, it’s clear he’s putting our hometown on the front lines of his attack on voting. And that’s exactly what we’ve called it in our coverage.

This isn’t partisanship. Our journalists don’t play favorites in our coverage. We are, however, proudly pro-democracy. We believe people who are eligible to vote and want to vote should be able to vote, and that it should be easy, safe, and secure for them to do so.

It’s also not our job to present the system as perfect when it has its share of flaws. Covering the potential for chaos can help avert that outcome. Covering the fact that hundreds of thousands of ballot applications have been rejected as duplicates can prevent voters from inadvertently sending even more duplicates that further strain election officials.

We’ll continue to state facts as facts as Election Day nears. And when the polls close, we’ll make sure our audience knows exactly what the early returns mean — and exactly what they don’t mean.

Dan Hirschhorn is senior politics editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer.