A protestor takes part in a peace march through Chicago's South Side. Trump's claim that violence in Chicago is worse than in the Middle East is one claim that the Guardian US’s Mona Chalabi showed readers how to verify in her “Just the Facts” columns

Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer, reporters on one of 2016’s most important news stories, the Panama Papers, recently issued a challenge in an essay published in The Guardian to their American colleagues covering President Donald Trump: Unite. Share. Collaborate.

The reporting pair from Munich’s Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper implored journalists in the White House press briefing room to rally together. Keep repeating previously ignored questions. Work together on joint news projects, like examining Trump’s ties to Russia or his international business connections. Partner with international journalists who may know more about a business affiliation in another part of the world. Take these steps “even if doing so might mean embracing something quite unfamiliar and new to American journalism,” they wrote.

In 2016, Obermaier and Obermayer shared data from a leak of more than 11 million documents from one of the world’s largest offshore law firms with more than 400 journalists. The resulting news stories—which, they declared in The Guardian, was “too big and too important to do alone”—showed how the rich and powerful exploited offshore tax havens and hid money.

The early weeks of the Trump administration highlighted the rocky relationship between the president and the media, prompting news organizations, already scrambling to shape new approaches to political coverage following the shortcomings of last fall’s election, to develop new approaches to reporting on the White House. These efforts come at a time when trust in the press has plummeted to an historic low. According to a 2016 Gallup survey, Americans’ trust and confidence in media dropped to its lowest level in Gallup polling history, with only 32 percent saying they have a great or fair deal of trust in the media.

While some news organizations are reassigning a reporter or two, others are creating whole teams. The Washington Post doubled the size of its America desk from six to 12 to cover breaking news outside the Beltway, adding a “grievance” beat to report on the anger—and the systematic changes in government, industry, and culture that have incited it—that led so many Americans to vote for such radical change in the White House. The New York Times is creating an immigration team and plans to hire a religion and values reporter outside of New York City. CNN is launching a new investigative unit, with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists Carl Bernstein and James Steele as contributing editors, and expects to add up to a dozen reporters. BuzzFeed has hired journalists to cover the relationship between the president and the press. Politico announced in December that it would have a seven-person team covering the White House, the largest White House coverage team in its history. The Marshall Project is hiring a bilingual reporter to examine the intersection of immigration and criminal justice.

To explore how news organizations are innovating to continue being a check on government as well as to connect government policies to the people affected by them, Nieman Reports explored six newsroom initiatives: Spaceship Media, a California-based journalism engagement start-up, is connecting people across party lines using social media; NPR and The Federalist are working to bolster coverage of middle America; The Arab American News is covering the experiences of Muslims directly impacted by the rhetoric and policies of the Trump administration; The Guardian is coaching readers in fact-checking skills; and MuckRock, a government transparency group, is strengthening the network of journalists working together to maximize access to public information.

These efforts move reporting out of the White House press briefing room and into local communities, offer more nuanced coverage of people impacted by government decision-making, strengthen watchdog journalism efforts, allow people to participate in journalism, and, ultimately, may also enhance trust in the media.

Covering the Partisan Divide

While national news outlets scramble to recover from stumbles during the presidential election, restore credibility, and adapt to a dynamic national political story, local news outlets are mapping ways to engage citizens and deepen trust.

Eve Pearlman and Jeremy Hay of Spaceship Media, a new California-based journalism engagement start-up whose mission is to spark dialogue between divided communities, wanted to do more than chronicle the divide between Trump and Hillary Clinton supporters after the election. They wanted to bridge the gap. So the co-founders of Spaceship Media reached out to Michelle Holmes, vice president for content at Alabama Media Group (AMG), which includes The Birmingham News, The Huntsville Times, and Press-Register of Mobile, with the idea of connecting voters across state and party lines in moderated discussions. The day after the 2016 presidential election, they started to design what became the Alabama/California Conversation Project.

Pearlman and Hay recruited 25 women from Alabama who supported Trump and 25 women from the San Francisco Bay Area who supported Clinton and brought them together in a closed Facebook group. All the women were asked the same questions: What do you think of the other community? What do you think they think of you? What do you want them to know about you? What do you want to know about them?

Based on this information, the Spaceship Media/AMG team created a video of all the stereotypes each group applied to the other. Then the organizers brought the women together for moderated Facebook conversations. Some of the women participated daily, others jumped in every few days. The conversations started immediately and continued at a rapid pace on issues that divide citizens: immigration, race, abortion, gun control, the role of the federal government, news sources. The conversations ebbed and flowed over the course of days and weeks. “Just like every other community, some people are very active, some not so much, and some active most about the topics that they were keenly interested in,” Pearlman says. Pearlman adds that the women became a community, “concerned about and interested in one another.”

Helena Brantley, an Oakland-based book publicist, decided to participate to gain a better appreciation of the perspectives of Trump supporters. “I felt like I did not know anyone in my family or social circle who voted for the president,” she says. “I wanted some insight into what led people to vote for him.”

Brantley expected the exchange would be challenging. The women talked about a range of topics, including Trump and Clinton. For many of the issues that emerged, journalists from AMG wrote news stories posted on AL.com. When the discussion moved to immigration, for example, journalists wrote stories that discussed issues such as the amount of taxes undocumented workers pay.

As complex discussions heated up on issues like the Affordable Care Act (ACA), local journalists from both AMG and Spaceship Media introduced reporting to provide context and build understanding. One of the key reasons Alabamians gave for their support of Trump, according to Holmes, was that he promised to do away with the ACA. Clinton supporters, on the other hand, saw Obamacare as largely positive. “So we did reporting that showed how the rollout in California had reduced the number of people in the state without insurance and how premiums and out-of-pocket costs were rising less rapidly in California, while the reverse was true in Alabama,” says Pearlman. “By introducing this reporting into the group women could see that the other’s support/opposition to ACA was not crazy but rather an outgrowth of their experiences on the ground in their own lives.”

Jaymie Testman, an Alabama transplant who previously lived in California, credited the journalists for providing meaningful context. “It was neat to get solid information,” says Testman, a Marine Corps veteran and mother of three teenagers. “They did some fantastic research. You got knowledge. They just tried to provide facts without taking any sides.”

Ultimately, the Alabama women were able to see how many more people have health care, and the California women were able to see how difficult it was for families in some areas of Alabama to pay the premiums. “Each side saw that Affordable Care Act looks different in each state,” Pearlman says. “They trusted our reporting … We see this as a victory for how relationships and deep engagement can help restore trust in the media.”

These efforts move reporting out of the White House press briefing room and into local communities

Reporters say they had reservations about whether the approach would have any impact but came to appreciate the importance of the effort. “I was skeptical at first, it seemed like such a Pollyanna idea to put a bunch of women in a virtual room together to hash out the issues dividing our country,” says Anna Claire Vollers, who wrote several of the stories for and about the group. “As the weeks wore on, we all started having ‘aha’ moments as we realized, through reporting and through their conversations, that where we live can have a profound effect on our firsthand experiences of immigration or healthcare.”

Holmes says the response from readers has been encouraging and that convening women with geographic and political differences set a new standard for reporting on politics. “What can we do in local communities is facilitate the sharing of ideas and stories. We’re only beginning to scratch the surface. Breaking the old journalism model gives rise to incredible possibilities. Regularly listening deeply without a specific story agenda will make us better journalists with deeper connections and deeper understanding of the issues that matter most to voters.”

The formal convening ended prior to the inauguration, but the participants selected their own moderators—one from each side—and are still talking. They also recently started a book club, which is currently reading “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis.” Of one of her favorite people in the group, Testman says, “We agree on almost nothing. Once we started having trust and getting personal, then people started asking questions. I started looking at their questions as just a question instead of an accusation.”

Covering America Outside the Beltway

While Spaceship and the Alabama Media Group used social media to bring groups together, other news organizations are putting more boots on the ground to report on communities in so-called “flyover country.” NPR is building on a model created during the election to expand its coverage. “We’re now asking people around the country what they want the new president to know about them and their community,” says Mike Oreskes, NPR’s editorial director and senior vice president of news.

As an extension of “A Nation Engaged,” a national conversation about politics and government in which 17 public radio markets participated during the election, NPR hosted simultaneous live town hall events in Texas, Wisconsin, California, and North Carolina prior to the inauguration. The community conversations allowed NPR to tap into the issues of real people in communities across the country. The conversations included discussions about identity and what it means to be an American, economic opportunity, and America’s role in the world, among other topics. “We believe it’s important to keep the conversation going among our audience, as well as with people who may not regularly be part of our audience,” Oreskes says.

With more than 1,800 journalists in nearly 200 newsrooms across America, Oreskes believes NPR is uniquely positioned to facilitate those conversations. A major effort to do so is being made with the recent launch of the statehouse reporting project. Growing out of a reporting partnership with 18 member stations to cover the presidential election, the statehouse project—which currently has about 50 active participants at member stations across the country—is helping bolster both local and national coverage by sharing resources and expertise among newsrooms.

For example, after Trump issued his executive order banning residents from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States, NPR teamed up with its member stations to find out where each member of Congress stood. The teams searched for public statements, looked at Facebook and Twitter posts, and recorded all the opinions they could identify. NPR’s Congress tracker became a go-to place to discern congressional responses to the president’s actions.

Similarly, in March, NPR worked with member stations to record congressional opinions on the proposed new health care bill, which failed to win enough support in the House to move to the Senate. The NPR analysis turned out to be accurate: Most Republicans supported the bill, though some conservative Republicans thought it didn’t go far enough to repeal Obamacare; most Democrats opposed the bill but a few from districts won by Trump were less strident in their opposition.

NPR has gathered quotes to put all the information in one place—something that is beneficial for both local stations and NPR nationally, according to Brett Neely, NPR’s state politics editor: “We’re trying to find ways that we can take the local reporting and help [member stations] fashion a product that is a little deeper, so that it hits their local reporting needs but then also lets them compare other lawmakers state-by-state. It’s also used for NPR’s [national] reporting, because now we’ve got this Web tool that’s telling us, yeah, Republicans don’t really seem to have the votes for this bill.’ We got that thanks to the contributions.”

The Congress tracker is only one example that has grown out of the statehouse reporting project, which Neely oversees. NPR is leveraging its presence in local markets to report on emerging national trends, such as that of several state legislatures considering bills that would limit protests and increase penalties for protesters. NPR was able to cover the story ahead of other national outlets because station reporters were already closely following the issue, communicating with each other via a dedicated Slack channel and regular conference calls.

Beyond enhancing coverage, the fact that the project is connecting state political reporters and encouraging them to share what they’re working on is beneficial, says Neely: “Having something where you can go and talk to your peers who cover state governments in 40-plus states, I think that’s actually something quite unique, and it’s really helpful … The thing that I hear every time from reporters is, ‘Oh my gosh, we should have had something like this 10 years ago.’”

NPR's statehouse reporting project grew out of "A Nation Engaged," a national conversation about politics and government in which 17 public radio markets participated during the election

Mollie Hemingway, senior editor at The Federalist, a conservative news analysis website, says while some news organizations are parachuting into communities to figure out what they got wrong, the strength of The Federalist is its inclusion of multiple voices from around the country. The Federalist started with four people three years ago and now has a dozen full-time staff members who work from different locations plus a network of hundreds of contributors in communities across the country.

Founded by Sean Davis and Ben Domenech, The Federalist provides news analysis and offers three daily newsletters—The Transom, for political and media insiders; Inbound, about national security and foreign policy; and Bright, by five “center-right” women on pop-culture news—a morning email update, and a podcast, “The Federalist Radio Hour,” which has more than 40,000 subscribers, according to The Federalist’s website.

The Federalist’s 25 senior contributors are scattered across the country, in cities like Austin and Houston, Texas; Charlotte, North Carolina; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Brooklyn, New York; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Cheyenne, Wyoming; and in Illinois, Arkansas, New York, New Jersey, Virginia, and the state of Washington. Contributors include lawyers, professors, independent journalists, and those working for other media organizations, stay-at-home moms, a Lutheran pastor, a director of a nonprofit that finds families for abandoned children, an artist, a musician, a Harvard Extension School professor, and a former counterterrorism intelligence analyst. The strength of The Federalist, Hemingway says, is that its contributors represent a diverse geography and lived experience.

“Having one or two reporters stationed in the middle of the country isn’t going to cut it,” Hemingway says. “When we started The Federalist we were intentionally decentralized. We don’t have offices. We have people all over the country. We have the perspective that a lot of people inside the Beltway tend to be lacking.”

Hemingway disdains much of the hypercritical coverage of Trump and says The Federalist offers a nuanced alternative to the mainstream press. The Federalist’s approach to covering the Trump administration builds on its strategy to elevate the voices of citizens outside New York and Washington. “Because they are not full time ‘horse race’ political reporters, they’re not interested in the daily drama,” she says. “They are very interested in the policy debates. Now, because everything is shaken up, people seem more receptive to outside thinking. It’s a great opportunity to get new perspectives. We don’t need to hire someone full time who’s a generalist. We can surgically go out and get that different opinion.” Hemingway particularly highlights The Federalist’s efforts to amplify women’s voices. During the recent “Day Without a Woman,” when the organizers behind the Women’s March on Washington called on women to take the day off work on March 8, International Women’s Day, to show the economic power and value of women, The Federalist published opinion and analysis pieces about not going to work being a privilege for elite women that took attention away from such human rights abuses as female genital mutilation, honor killings, and sex trafficking. One writer opined about everything from the missing girls kidnapped by Boko Haram to the Ladies in White, the Cuban women who were arrested for peacefully protesting the capture of their husbands, fathers, and sons. Others wrote about the important “people-focused” work women take on as teachers, health care providers, or homemakers for which there is little or no pay but high value.

“I want to support the disenfranchised and the voiceless, the marginalized and the oppressed,” writes Gracy Olmsted, an associate managing editor at The Federalist. “That includes women who encounter sexism in the workforce, or lack of appreciation in the home.”

Olmstead continues, “But I will keep working: because being a mom isn’t something you just stop doing. And I’m glad I don’t get to take a break.”

A 2014 Pew research report pointed to limited news options for conservative audiences, a business opportunity leaders of The Federalist were keenly aware of when the publication was started, Hemingway says. The Pew study found that conservatives and liberals turn to and trust different sources of news and information and that conservatives had fewer sources. In the study, people identified as “consistent conservatives” were “tightly clustered around one main news source” with 47 percent of respondents citing Fox News as their main source for news about politics and government while “consistent liberals” cited a range of primary news sources.

The Federalist attributes its dramatic growth to content that connects with an audience hungry to see conservative views represented. “Our media haven’t done a good job of finding out why people are dissatisfied,” Hemingway says. “A lot of people who write or work for us were not supportive of Trump but were supportive of ideas that come from outside the Beltway. We wanted to highlight the wisdom of the rest of the country.”

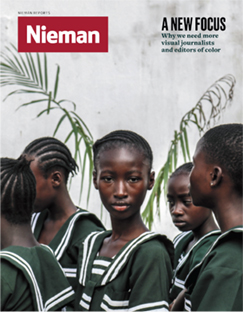

Covering Minorities

While Muslims, Latinos, and Native Americans have been directly impacted by some of the new administration’s most controversial policies, only a few news organizations have announced plans to expand coverage of race and ethnicity. Few resources are being permanently redirected to specifically engage Muslim communities impacted by the Trump administration’s travel ban or members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe impacted by the executive order expediting completion of Dakota Access Pipeline or Latinos affected by aggressive deportation policies. Many investigative and national teams have little staff diversity, renewing questions of trust and credibility in diverse communities. Frustrated by the historical absence of Arab American and Muslim voices in news coverage, Osama Siblani, publisher of The Arab American News, is pushing to make sure the experiences of Muslims are included in the national conversation.

The Arab American News, with a staff of 25, is focused on chronicling the life experiences of Muslims and Arab Americans locally and nationally who have been impacted by decisions of the Trump administration. Much of The Arab American News coverage since Trump’s inauguration has focused on attacks on the rights and well-being of Muslims. In the month following the election, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported a surge in anti-Muslim hate crimes and hateful letters sent to mosques and Islamic centers, which follows a 67 percent increase in hate crimes against Muslims in 2015, according to the FBI.

The Arab American News’ content priorities are to not only document attacks against Muslims but to capture new support of Muslims and Arab Americans

Following the travel ban, news organizations scrambled to tell stories of everyday Muslims living and working in America, stories Siblani has worked to tell for more than three decades. He blames the press for what he calls a warped portrayal of Muslims, images that have ignited a “climate of hate” and intolerance and helped give rise to Trump. “Our community is under attack,” Siblani says, adding that women who wear hijab are most targeted. “We are documenting all these attacks and all these violations of our civil liberties and civil rights. It has been like this for a long time. We came here because we wanted to leave trouble behind. People are not registering for their medicine or social security benefits because of their fear of being targeted. They’re not talking to other media or organizations. They feel comfortable coming to our organization because we have people who look like them, talk like them and understand their needs.”

The Arab American News’ content priorities are to not only document attacks against Muslims but to capture new support of Muslims and Arab Americans, according to Siblani. One recent story focused on a Dearborn, Michigan woman who started a yard-sign campaign to show appreciation for her Muslim neighbors. Dearborn, a city of 98,000 residents that borders Detroit, is home the Islamic Center of America, one of the largest mosques in the United States, and is considered the informal Arab and Muslim capital. The sign reads, “No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor.” The group posting signs had grown to 500 people. Jessica Woolley has 10 volunteers who help distribute the signs. “These are social stories that help rally the entire community and stories that say you’re not alone,” Siblani says. Few, if any, other outlets are covering that story.

Siblani, who has described himself as an “activist journalist” and says his coverage is biased in favor of Arab Americans he feels are not represented or misrepresented in the mainstream media, is hopeful that the coverage his outlet provides will increase civic engagement and political involvement. There are signs that change is happening. In 1985, Michael Guido won the race for mayor of Dearborn on an anti-Arab platform, distributing a pamphlet promising to address the “Arab problem.” Today, Arab Americans have leadership roles on the Dearborn school board, city council, police department, and local court, and a 32-year-old Michigan-born Egyptian doctor, Abdul El-Sayed, recently announced a run for governor in 2018.

Collaborating on Coverage

The Guardian US’s data editor, Mona Chalabi, has received so many requests from readers to verify information in the weeks since Trump’s inauguration, she rolled out a step-by-step, do-it-yourself guide showing readers how to independently verify information on their own. “It’s not enough to say, ‘Take my word for it,’” Chalabi says. “Methodology is more important than ever.”

Despite the many fact-checking services available, Chalabi finds that the questions she most often receives are about how people can find out for themselves. So she launched her “Just the Facts” column, which sets out to empower people with skills that will enable them to reach their own conclusions.

In one recent column, using President Trump’s statement that violence in Chicago is worse than in most Middle Eastern countries, she instructed readers in how to research Chicago segregation data, pull crime maps to determine the city’s crime rate and to find data on homicide rates not related to armed conflict. She then told readers to make sure numbers from different sources compared the same things and to search for an historical perspective as well as context.

In one of her most popular columns, Chalabi decided to investigate the frequency of crimes committed by immigrants. Prompted by Trump’s suggestion during his speech to Congress that the rate of crimes perpetuated by undocumented immigrants was so high that it required a federal office to address it (he announced that he had ordered the Department of Homeland Security to create VOICE—Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement), Chalabi didn’t want to just tell readers what she found, but how she found it. She walked readers through each of the six steps of her process: find out what exactly Trump said, find out which immigrants he is talking about, research correlation, find out how often undocumented immigrants in the U.S. commit crimes, find out how often native-born people in the U.S. commit crimes—and find out if this matters.

Chalabi meticulously outlines her sources for each step, and links to each of them so readers can take a look for themselves. In step three, for example, where she researches correlation between crime rates and the number of unauthorized immigrants in the country, she writes: “I search for ‘undocumented immigrant crime rates’ which takes me to a New York Times article, but I don’t spend much time there – I quickly click through to find the original source of that journalism. I end up on this page [with a report about the criminalization of immigration] from the American Immigration Council. Before I do anything else, I go to their ‘about us’ section and find out that this is a nonprofit organization, but its self-description sounds like it’s pro-immigrant so I should keep that in mind.” She goes on to cite the statistics she finds and where she double-checks this information.

Ultimately, Chalabi found that first-generation immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than native-born people in the U.S. For second-generation immigrants, the numbers are the same as native-born people. She ends her column with step six, finding out why this matters—referencing an article from Democracy Now that notes the link between the Trump administration’s plans to publish a weekly list of crimes committed by undocumented immigrants and similar lists Nazis published on Jewish crimes. While Chalabi expects to continue this kind of work, she hopes her blueprint gives readers greater confidence to verify or refute the news they hear. “It’s about not just walking away with information but walking away with skills,” Chalabi says.

Her editor, Jessica Read, adds that doing so can help provide a foundation of trust for audiences, and at the same time help fight the misinformation swirling through people’s newsfeeds. “We see Mona’s column, and her skills, as the perfect antidote to the parasitic fake news currently engulfing our media landscape,” says Read. “Not only can she demystify a quandary for our readers, but she can also teach them how to find the right resources and procedures to verify a story on their own. I can’t think of a more pressing issue in journalism than the question of trust. Mona’s column works to build the trust readers should put in any reputable news outlet.”

“It’s not enough to say, ‘Take my word for it.’ Methodology is more important than ever.”

—Mona Chalabi,

The Guardian US data editor

What Mona Chilabi is doing for fact checking, Michael Morisy is doing for FOIA requests.

Morisy, cofounder of MuckRock, a government transparency group that helps media outlets access public records, thought the transition between administrations would be an ideal time to create a channel for news organizations to share information. Morisy issued an invitation for journalists to join the group’s Slack channel. More than 3,000 people signed up. “We decided we wanted to show people the public records process,” Morisy says. “It made sense to try to build up a stronger Freedom of Information Act community across newsrooms. Whether you are a traditional journalist, someone with an ideological bent or an individual, public records are for everyone.”

Journalists are using the channel to request, analyze, and share information and to support, collaborate, and discuss how best to handle records requests. The immediate impact has been that journalists from different news organizations are working together rather than competing. Among the collaborations, journalists have screened 144,182 pages of Department of Justice documents on Neil Gorsuch, brainstormed on a “transition FOIA” thread about which stories to pursue on a GOP Obamacare Repeal talking points document, and helped each other craft a number of FOIA requests targeted at specific agencies based on different reporters’ beats as well as announcements of the new administration.

Given how slow responses to FOIA requests can often be, many of the stories that may come out of those requests are still in progress. But just as interesting are the stories that come out of requests that have been rejected. This happened after Michael Best, a writer and analyst covering the intelligence community and national security issues (and an avid MuckRock member), requested FBI files related to media companies associated with Trump’s pick for secretary of the treasury, Steve Mnuchin. The FBI denied the request, saying the documents requested were exempt from disclosure because they were involved in a law enforcement proceeding—something the Senate took notice of after Best reported on it. During Mnuchin’s confirmation hearing, Senator Sherrod Brown questioned the hedge fund manager about whether he was involved in a federal investigation. Mnuchin denied it, but Best’s further analysis of the language in the FBI’s written response of their FOIA rejection suggested otherwise. Best’s work was originally posted on MuckRock and on his own website, Glomar Disclosure, and was reported on by outlets including Deadline and The Hill.

Morisy also credits lively discussion on the Slack channel with bringing more exposure to issues like the FBI’s new policy to no longer accept FOIA requests via email, forcing requesters to rely on snail mail and fax machines instead. Coverage of the subject by The Daily Dot and TechCrunch referenced MuckRock to illustrate what a huge step backwards it was for the FBI to revert to archaic communication methods for requests.

Morisy hopes the enthusiasm around public records requests will lead to greater collaboration among journalists. “We’ve pushed journalists and newsrooms to try to act more collaboratively and more transparently,” he says. “We think it helps build trust with your readers. Making sure the public has access to what the government is up to is more important than ever.”

Bastian Obermayer, who along with Obermeier led coverage of the Panama Papers, couldn’t agree more. “We don’t want this to make it seem like there’s a war with Mr. Trump,” he says. “For journalists, it’s not being at war, it’s being at work. The work is to check the government.”