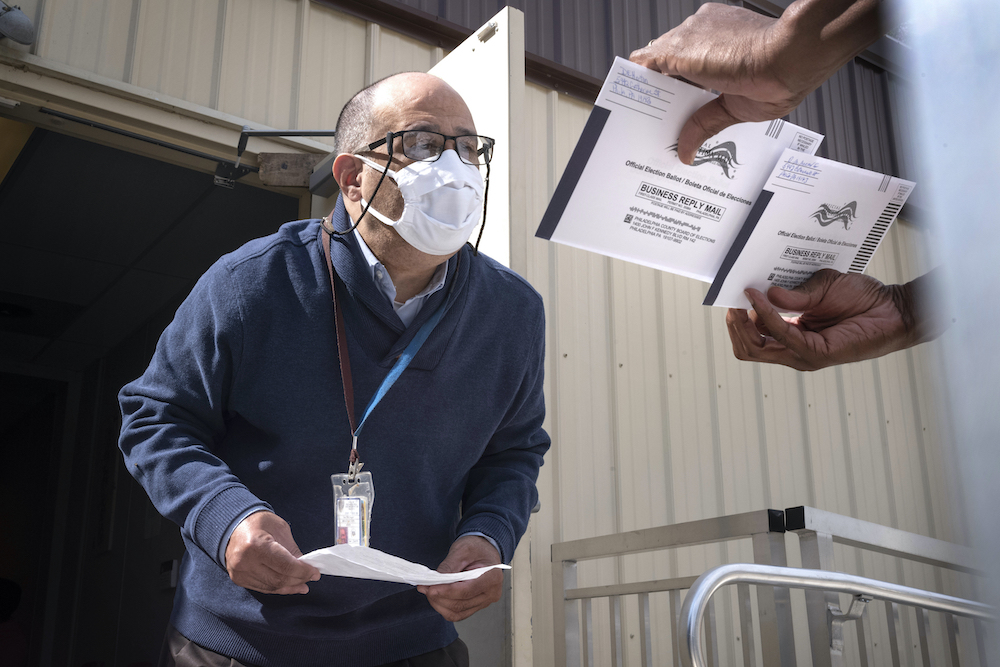

An employee of the Philadelphia Commissioners Office examines ballots at a satellite election office at Overbrook High School on Thursday, Oct. 1, 2020, in Philadelphia. The city has opened 17 satellite election offices where voters can drop off their mail-in ballots before Election Day

David Lauter, Washington bureau chief at the Los Angeles Times, is not preparing for Election Day — he is preparing for election week, or even election weeks. Most election cycles at the paper have followed a more succinct timeline: Political reporters make it across the finish line of the first Tuesday in November, then they take what Lauter describes as “a well-deserved vacation.” But this year is different.

“Typically, on Election Day, we prepare a couple different versions of a story with alternative ledes so when you know the result you can publish something quickly. This time around there are several more scenarios you need to plan for, and you also need to plan staffing with an eye towards the possibility that maybe it’s Wednesday, maybe it’s Thursday, maybe it’s the following week, maybe it’s longer before we know how all of this ends,” says Lauter.

There are, to put it mildly, some unusual variables for political reporters and newsroom leaders to consider this election season

The L.A. Times is one of many newsrooms across the country currently bracing for a potentially chaotic election period, which has seasoned journalists on edge. The New York Times has created a “Daily Distortions” page devoted to debunking viral misinformation in the weeks leading up to the election, is crafting its vote modeling system to clearly convey uncertainty where it exists to readers, and will have 20 reporters pre-positioned in battleground states. At BuzzFeed News, political editor Matt Berman says the newsroom has taken on an “all hands on deck” mentality: “We’re in part taking an approach that’s similar to how we handled the first months of the coronavirus pandemic, in that every reporter in the newsroom is taking on some piece of this election under the assumption that it is very possible that election night and election week might be unprecedented.”

There are, to put it mildly, some unusual variables for political reporters and newsroom leaders to consider this election season. For one, a significant number of voters are expected to cast mail-in ballots due to the coronavirus pandemic; in some states, including key battleground states like Pennsylvania and Michigan, there are rules preventing those ballots from being tallied or legitimized too far in advance of Election Day, meaning results may be delayed by days or even weeks. This would not in itself be cause for alarm, but the Trump campaign has baselessly cast doubt on the legitimacy of mail-in ballots, and lengthy delays increase the likelihood of him or his base crying foul if it seems waiting for conclusive results could hurt his chance at victory.

Part of preparing for any disinformation-induced disruption has begun with rigorously debunking false claims in the weeks prior, notes Lauter. Trump has specifically targeted California, baselessly claiming the state gives ballots to “people who aren’t citizens, illegals” and “anybody who is walking or breathing.” The L.A. Times has responded by reporting on those claims in a straightforward manner that underscores their illegitimacy. The California Republican Party, meanwhile, has admitted to distributing fake ballot boxes around the state — the kind of potentially illegal activity the party’s presidential candidate has falsely accused Democrats of perpetuating.

As is always the case when reporting on disinformation, journalists weigh the necessity to inform their readerships with the risks of giving a platform to falsehoods. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, says Lauter — each instance is evaluated on a case-by-case basis: “I think you have to judge how much impact the issue you’re writing about is having. Is it something that’s having a major impact on the campaign, in which case you can’t ignore it? Is it something that people aren’t going to be hearing about if you don’t write about it, or is it something that’s so widely out there that the risk of spreading it is less significant because it’s already been spread?”

Disinformation about mail-in voting falls into the category of things that should be covered, responsibly and with an abundance of clarity — it has an enormous potential to impact the election and is being proliferated by the president himself.

L.A. Times reporters will likely be pre-positioned in certain places where ballots may be challenged the morning after election night, Lauter explains — battleground states like Pennsylvania and Arizona, for instance. “I think we’re doing more planning now with an eye towards where we’re potentially going to want to have people Wednesday morning in case this is unresolved,” he says. “That’s actually more of the planning and staffing exercise than election night itself.”

The Washington Post is making similar preparations, according to the paper’s deputy national editor, Lori Montgomery, given the possibility of a fraught, extended election process. “We already have a team of four reporters focused on the voting process, election law, and the legal battles over how votes will be cast and which votes will be counted. And we are assembling a much larger team to report on the ground from dozens of states likely to experience difficulties on Election Day or extended vote counts,” she wrote via email. “The whole staff is also bracing for the possibility of massive post-election conflict if, for example, a key state like Pennsylvania is unable to certify a result, and the election is thrown to the courts as it was 20 years ago.”

There is also the question of how to present shifting results to readers in real time as the votes roll in over days or weeks. A recent Axios report found that many media companies, given the uncertain nature of the election, have planned to focus on tracking those real-time developments over predicting results. The Washington Post built a vote modeling tool called “Expected votes tracker,” which is designed to convey that uncertainty, keeping readers informed about where there may still be votes outstanding.

Early voters line up at a church in West Lake Hills, Texas, during the first hours of early voting on October 13, 2020. Texas is one of the few places in the U.S. not allowing widespread mail balloting during the pandemic

The L.A. Times Data Desk is prioritizing transparency and clarity, says data reporter and developer Ryan Murphy — how can they demystify the process for readers who may be anxious and confused? The reality is, “Maybe we won’t have a clear answer November 3,” he says. “How do we think about that in terms of what we present on our results page? And I think more importantly, how do we help people understand that by design this is part of the process, it takes time to count, and help guide people through the realities of that?”

The Data Desk is still working out specifics, but ideally readers will be able to dip in and out of the results page and see what changes have taken place since they last visited the page — the average reader will likely not be glued to the screen, Murphy says, but will want incremental updates: “We’re thinking about, how can we show those changes over time and give context to them? … If it does take two weeks for us to give a clear picture, how can we guide people over those two weeks?”

BuzzFeed’s Berman says reporters on a variety of beats are pitching in to accompany the more traditional campaign coverage, both in terms of stories leading up to the election and anticipation of the election itself. There are teams dedicated to looking into the spread of disinformation on social media platforms, as well as voting rights and voter suppression issues — including disinformation from Trump regarding mail-in ballots.

“We have a lot of people who are taking on different parts that are a little bit different from the traditional campaign beat, and that’s all in addition to the traditional campaign beat where we have people who are on the campaign team who are traveling as much as we can safely, talking with voters, talking with campaign sources, doing that sort of coverage as well,” says Berman. BuzzFeed News is also one of several outlets that, following Trump’s coronavirus diagnosis, pulled their White House reporters from the press pool that would normally be traveling with the president due to the health risk.

The election teams also include journalists focusing on the potential for militia violence around the election, given Trump’s encouragement of followers to “go into the polls and watch very carefully,” which experts fear could lead to armed militias guarding polling places. Law enforcement officials have expressed fears that the heated climate could lead to an outbreak of post-election political violence. Preparing for such a possibility is tricky, according to Berman, prompting editors to make practical and ethical judgments that weigh the necessity of preparation against the potential for fear mongering.

“It’s a really hard thing to plan for and write about because you want to be really careful not to assume that there’s going to be conflict, because that could also prompt conflict,” Berman says. “You don’t want to scare people away from voting, which I think is an easy trap for some places to fall into, and you don’t want to assume the worst — but you need to also prepare for it.”

There is also the question of how to present shifting results to readers in real time as the votes roll in over days or weeks

Montgomery says the Post is bracing for conflict as well, but there’s only so much preparation one can do on that front. It is largely a matter of keeping in touch with sources and remaining vigilant, she says: “Finding and covering instances of voter intimidation and election-related violence is also top of mind, and we have several reporters keeping in touch with law enforcement, monitoring social media and digging into individual counties with a high likelihood of attracting an armed presence on Election Day and beyond. We also continue to scan the waterfront for foreign interference.”

Newsrooms seem caught between competing incentives — the need to prepare for worst-case scenarios to the degree that one can without increasing the chances of those scenarios unfolding, the need to cover disinformation campaigns without amplifying disinformation, and the need to prepare for chaos while bearing in mind that there could very well be a landslide victory on election night one way or the other.

One politics editor at an online news site, who asked to remain anonymous so they could speak freely, was frank about the pressures: “It’s stressful.” This editor has assigned explainers on the intricacies of mail-in ballots, is preparing to present live results while informing readers of the limitations of those results, and is gearing up for the possibility of civil unrest.

“We were discussing, how do you pre-write election night when so much of it could be very well based on states that haven’t been called?” the editor says. “I’m exhausted, I know my writers are exhausted. We’re already thinking about, how are we going to rotate people to make sure we have coverage at all times, while still giving people breaks and trying to keep them as fresh as possible? This might be the first time as a journalist I’m ever hoping for the boring outcome.”

Allegra Hobbs is a writer based in Marfa, TX who covers the media for Study Hall.