Ruth Cowan, circa 1947, holds a copy of The Guild Reporter

During my Nieman year, I spent Spring break in Harpers Ferry, a town of 300 in West Virginia. I went there looking for traces of Ruth Cowan, the World War II correspondent with whom I was obsessed and after whom my Nieman fellowship was named. There I knelt in front of her grave, and I touched her typewriter.

It was a cold morning when I softly pushed the keys after putting the type-bars back into place. The letters “Underwood” on top were almost white after years of dust. There were pockets of cobwebs around the edges. I barely could move the 28-pound typewriter as I inspected it for the first time.

The typewriter sat by the window in a white house in the woods just outside Harpers Ferry. Its owner is now Carol Gallant, one of Cowan’s neighbors. She is one of the few people left who knew Cowan, who had few relatives, married at 56, and never had children.

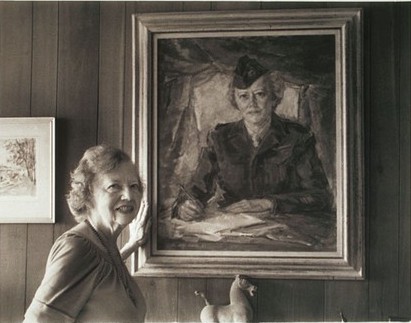

Cowan stands in front of a painted portrait of her in an Army uniform

In the age of #metoo and strong female leaders, it is easy to forget how much extra effort was required for Cowan to even be allowed to cover serious news. She was a war correspondent and crime reporter when a female reporter was expected to cover the fashion choices of politicians’ wives. Women are no longer considered a rarity in newsrooms and there is no position out of reach, but still most of the editors at the largest publications are male and the pay gap persists. Cowan’s way forward—speaking up at times and joking about injustices—will sound familiar to anyone overlooked for their gender, skin color, or national origin.

Cowan is barely remembered today, her career dissolved in history by the storytellers of her time, most of them men. The effort to record the neglected accomplishments of those out of power remains a struggle. But the stories of strong women are essential to empower those of us who don’t have the advantage of being in a dominant group.

When I got to West Virginia, I had already spent many hours with Cowan’s manuscripts, pictures, letters, and tax returns at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library at Harvard. Her portrait hangs in a meeting room by the entrance to the building. The portrait could be in a better spot. I saw it for the first time through a windowed door after several visits to the library.

In the painting, Cowan holds a pencil with a notebook open in front of her. She wears a military uniform, including the hat. It is an unusual outfit for a reporter, but she was required to wear the same uniform as the first women deployed with the U.S. Army. She was the first female reporter to accompany them. She was in her early 40s when she went to North Africa to write for the Associated Press in January of 1943. In the portrait, she looks older. Still, she is shown with her hair perfectly blonde. She loved to mention how she struggled to keep her dyed color neat during the war and how she mixed the chemicals in her helmet.

In the age of #metoo and strong female leaders, it is easy to forget how much extra effort was required for Cowan to even be allowed to cover serious news

I received the fellowship named after Cowan because I fit into the purpose that she and her husband, Bradley Nash, established when they made a donation in the early 1980s to the Nieman Foundation: Cowan wanted to help foreign correspondents. That is probably the shortest definition of the first part of my career.

I share with Cowan the uneasiness, sometimes the privilege, of the outsider. Though born in Spain, I have lived, studied, and worked mostly in the U.S., torn between a complete sense of belonging and a foreigner’s unease. I don’t fit into a box. And that’s often a problem. Cowan was pressed to conform to her role and cover “the women’s angle.” That doesn’t happen anymore, but there is pressure to conform in other ways. If you want to be taken seriously in Spain, you have to cover national politics. If you are born in a Spanish-speaking country and you live in the U.S., you probably need to write a book on crime cartels in Mexico. That’s what I have experienced. Conform, conform, conform—to what you are, to what you are supposed to be.

Cowan fascinated me as a woman who seemed fearless in an era that didn’t reward that. She covered World War II against the odds, against the military, against several editors. She overcame most of that, but not enough to be remembered by history.

Kent Cooper, the general manager of the Associated Press from 1925 to 1943 and afterward executive director, started hiring women at the AP, including Cowan. But in his 325-page autobiography, published in 1959, there is no mention of this fact. No mention either of Cowan or any female reporter, although there are several chapters about the “fine men” who covered the war for the AP. The book has dozens of pictures of journalists, editors, and politicians. All of them are men, white men.

Not only was Cowan a pioneer in traveling with the U.S. Army during the North African invasion, she was also one of the few American reporters of any gender who covered the war, from January 1943 to the summer of 1945, without a break. She was based in London for most of the war and reported from England, France, and Italy. She was on the shores of Normandy before most of her male colleagues.

Her career was exceptional for a woman. She interviewed Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1928 Democratic convention in Houston. She chronicled the Al Capone trial and wrote about markets in Chicago. She filed daily from Washington. She was pen pals with Eleanor Roosevelt.

Cowan cared about being recognized and remembered. She started writing a memoir about her experiences in the war. Her manuscript was rejected by a publishing company with the excuse that there were too many books about the war. It was 1946, and those books were written by men.

The 118 pages of Cowan’s unpublished “Why Go To War?” are hard to put down.

“Why any woman of my age and dependent upon an expert beauty parlor to keep her blonde hair looking ‘so natural’—or even blonde at all—should want to go to war of her own accord is something I’ll never understand,” Cowan began. “But go to war I did, and at considerable trouble. Furthermore, I had a lot of trouble staying at the war.”

That trouble was mostly caused by generals, editors, and colleagues who didn’t want women around. The Roosevelt administration wanted female reporters to write about the first military division in the U.S. Army made up of women, initially called the Women Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and then Women’s Army Corps (WAC).

Cowan writes in her notebook while covering WWII in Virton, Belgium in 1944

Cowan and Inez Robb, a columnist, were the first two women officially credentialed to cover the war in the fall of 1942. They were regarded by the government as propaganda tools to recruit more women or at least get their support. Cowan’s picture, with her military uniform, was on the front page of The Washington Post on January 29, 1943 under the headline “Ready for War…”.

Other female reporters profited from the new openings, but Cowan had the hardest time and stayed the longest.

Her first hostile editor was Wes Gallagher, in charge of the AP office in North Africa, who greeted Cowan’s arrival in Algiers in January of 1943 by saying that a woman could not stay there. Cowan even accused him of trying to kill her by placing her in a position he knew was going to be bombed. She wrote, and probably never sent, a telegram complaining to Eleanor Roosevelt and advising other women not to go to war. Gallagher later became president and general manager of the AP.

Hal Boyle, a colleague at the AP who won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the war, was outspoken against female reporters. He died in 1974, but recent articles celebrate him and there is an award in his honor for best newspaper or news service reporting from abroad given by the Overseas Press Club. Boyle wrote a piece with the headline “I Hate Women War Correspondents—But.”

“Women war correspondents would be wonderful–if they just weren’t women,” he started. “They have improved their hair-do through the centuries, but women war correspondents are still women. Many of them are braver in the field than men reporters, many are better writers, but sooner or later they show that underneath their correspondent’s patch lurks ‘womanhood.’ And ‘womanhood’ has no place in an active war zone.” He made exceptions for “sweet Ruth Cowan,” “gentle Lee Carson,” “shy Ann Stringer” and “blonde Iris Carpenter.”

The reluctance to consider women as equal happened also within the military. The smear campaign against the female unit is well documented in the official Army chronicle, as journalists and soldiers portrayed women as a threat to men, morally unfit, or too weak to fight. There were complaints even about the “burden” of separate toilets for women. “Latrines are an alibi. It is a way to keep women—their own women—away from war zones,” Cowan wrote.

This sounds familiar even now. Photojournalist Lynsey Addario recounts how she wanted to cover the war in eastern Afghanistan in 2007 and an official informed her she couldn’t because there was “no place” for her to “go the bathroom” in the bunkers where men lived. She went anyway.

The gender imbalance affected the coverage on the ground. Having a female reporter was the only chance of setting the record straight about the role of women in the war. “It was a woman who would lead a Nazi officer on and then kill him. There was a girl not yet twenty years old who could murmur softly and then drag her blood dripping paratrooper knife across her arm,” Cowan wrote. “It is their stories I want to tell.”

Cowan was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, on June 15, 1901. There is no birth certificate. She had some trouble getting a passport because of that, but I think the date is accurate because of a tiny piece of eaten up newspaper I found at Radcliffe. Her father, William, was a mining prospector who didn’t have much luck. He was described as a bartender at his death, when Cowan was a teenager. Her mother, Ida, worked as a teacher and tried to make money on a farm in Florida while Cowan stayed behind at a Catholic school in San Antonio, Texas. Cowan mostly lived on her own from the age of 13.

Cowan is barely remembered today, her career dissolved in history by the storytellers of her time, most of them men

Like the new women of the 1920s, Cowan had her bob-cut hair and wanted a good job. She supported herself as she studied and worked as a clerk or librarian. She attended the University of Texas in Austin, one of the most progressive, diverse colleges at the time. She often encountered talented women who helped her with encouragement and even money.

Her first byline, or the first one I found, was in the June 1920 issue of The Longhorn Magazine, a monthly containing poems, essays, and features. Cowan’s story is called “The Indian Ghost at Fort Marian.” The headline made me suspicious: Indians instead of Native Americans, ghosts as a cliché, and a typo (it’s actually Fort Marion). But the story tells a very different tale. There are no ghosts, the villain turns out to be a white man, and there is a condemnation of the brutality from the Spanish colonizers against Native Americans.

After graduating in 1923, Cowan started teaching high school, a natural path for working women then. At the beginning of that decade women accounted for 80 percent of the teaching profession in Texas. But Cowan wanted something else. Years later, Cowan explained why she became a reporter. “When one is young and has dreams in one’s eyes, one of the biggest is apt to be a desire to set the world on fire – a horrible idea in hot weather!” she wrote.

Money was an issue. She began writing movie reviews for the San Antonio Evening News “in order to afford coffee.” Cowan was very aware of discrimination observing that “the masculine paycheck” was usually bigger than “the feminine,” and that “a woman reporter is fine for the feminine angle, but it takes a man for the news.”

As she started freelancing for The Houston Chronicle, she signed some of her pieces as “R. Baldwin Cowan.” Using a masculine-sounding name was a way to get more money and more assignments from papers where editors hadn’t met her in person. But soon the first initial became “unhandy.”

Cowan was self-aware about her position, and she used gender discrimination in her favor, usually joking about it. One of my favorite letters is the one she wrote from Austin on April 1, 1929, to Kent Cooper, the head of the AP. She was applying for a job, any job. United Press had fired her shortly after a boss discovered that his reporter “Baldwin Cowan” was actually a woman.

The letter began: “Dear Mr. Cooper. First, I am a girl. Sight unseen I pass for a man. But notwithstanding my femininity I need a job, want one with the AP and can hold it … I never wrote a weather story that wasn’t rewritten. I snore at women’s luncheons, but I have no objection to exploiting the ‘woman’s angle’ in any field. But I like murders, politics, gang-wars and what-not with plenty of action. Never sat through a baseball game in my life … Am afflicted with ambitions. Want plenty of opportunity to train for big assignments and eventually want foreign service.”

Cooper was named general manager in 1925 and the next year assigned a woman, Ethel Halsey, to interview Helen Wills, the Olympic gold medalist in tennis. That changed the wire service’s policy and there began “the invasion of women,” as critics called it. The AP had employed women for decades as clerks, secretaries, and telephone operators, but not as reporters. Between 1928 and 1931, Cooper hired at least seven women. He wired back to Cowan offering her a position in Chicago. She was on “general assignment,” which meant covering “murders, gangsters, and of course, ‘the women’s angle.’”

Cowan covered World War II against the odds, against the military, against several editors

Chicago was one of the few places in the country where women got to do more hard news. The Chicago Tribune, in particular, gave women the opportunity to cover crime with an emphasis on “sarcastic humor, a cynical viewpoint and slang-infused prose,” as explained by Beth Kaszuba Fantaskey in her Pennsylvania State University dissertation, “Mob sisters: Women reporting on crime in prohibition-era Chicago.” For the first time, female reporters weren’t exploited as part of the story or forced to be “sentimental.” “These ground-breaking reporters of the Roaring ’20s didn’t use their gender to scandalize readers with the novelty of women getting close enough to killers to interview them,” Fantaskey wrote.

Cowan started working for the AP in Chicago on April 11, 1929, less than two months after the Valentine’s Day Massacre, when seven members of the mob were lined up in front of the wall of a garage and shot. “Somebody at the AP… thought it may be smart to find out just exactly how much this newcomer could take,” Cowan wrote. “They shipped me down with several other reporters to this inquest. I got in the thing and one thing that I do remember is the smell of formaldehyde. I didn’t like that and I never have liked that. It was the first time that I’ve seen that you could take a body, put it in formaldehyde in a drawer, stuff it on a shelf, and deep freeze it. They reached over and pulled one of the bodies out. … I went back and wrote about it. They said, ‘She did all right. She didn’t faint at all. Nor did she get sick.’”

Cowan was a novelty in the newsroom. “It wasn’t quite known what to do with a woman reporter—so I sat around getting shy and worried. I knew I had much to learn and had come a long way on initiative, courage and a willingness to work,” she wrote.

“I didn’t regard myself as a woman, and therefore should be limited in what I could think and what I could do and what I wanted to do,” Cowan said in a 1987 interview for the Washington Press Club. “And I think that’s a mistake so many gals make; they feel, ‘Well, I’m a woman, and they push me around.’ They don’t push you around any such thing; you push them back and go do your job, and you’ll get on the front page. And that was the thing to do.”

Cowan pushed to cover the biggest stories in Chicago and she started developing her own writing style. She was enamored of details, as good reporters are.

During the trial of Al Capone in 1931 she noticed he was moving slowly. She looked at his shoes. “Oh, new shoes. They hurt, don’t they?” she asked him. “Yes,” Al Capone said.

Cowan talks to a Polish woman in uniform during WWII

“I think curiosity more than anything else has been one of my strengths,” wrote Cowan. “You’ve got to have interest in people and what you’re covering. Furthermore, you’ve got to have sympathy for people. That doesn’t mean you have to be on their side. It means you have to try to understand why they did this, and what prompted it.”

She had strong opinions on “the women’s angle” over the years as she asked to be transferred to Washington.

“I do not believe the Associated Press is exploiting the so-called ‘feminine angle’ to its fullest possibilities in the wire news report from the viewpoint of stories, contacts or sales promotion,” she wrote in May 1937. “For a reporter who has fought consistently to be ‘treated just like a man’ in the matter of assignments, the idea of a woman’s editor attitude naturally is a bit hard to swallow whole.”

“Women reporters try and try to ‘get the breaks on assignments with the men.’ We have had to,” she said. “Women are people—and getting increasingly important in this country.”

Cowan spent 27 years at the AP, more than any of the women hired in the 1920s. Her retirement as a woman was compulsory at 55; men could stay until 65.

After leaving the AP, she married Bradley Nash, a government official who moved with her to Harpers Ferry. Cowan was the president of the Women Press Club in Washington and worked for the Republican Party and the Eisenhower administration, but gave up her adventures and mostly her writing. Her husband became the mayor of Harpers Ferry and a local celebrity.

Cowan had strong opinions on “the women’s angle” over the years as she asked to be transferred to Washington

The house in the forest where her typewriter remained was destined to be her place to write, according to Gallant, the current owner, but I didn’t find articles by Cowan after the 1950s. She never managed to publish her memoir.

She saved an elm in town and won several rose competitions. Among the scant papers preserved from her life in West Virginia, I found her membership card from the American Rose Society. She was entitled to receive American Rose Magazine, the latest edition of “A Handbook For Selecting Roses,” and “help on personal rose problems.” Cowan died in 1993; her husband in 1997.

I went to her grave next to Brad’s in the Harpers Ferry cemetery. The plaques on their graves are similar, bronze on stone, golden letters, a cross. Nash’s says “Lieutenant Colonel U.S. Army World War II” and has a little U.S. flag planted beside it.

Cowan’s grave is overgrown with grass and her plaque says, “Ruth Cowan Nash, beloved wife of Bradley D. Nash.” That’s it.