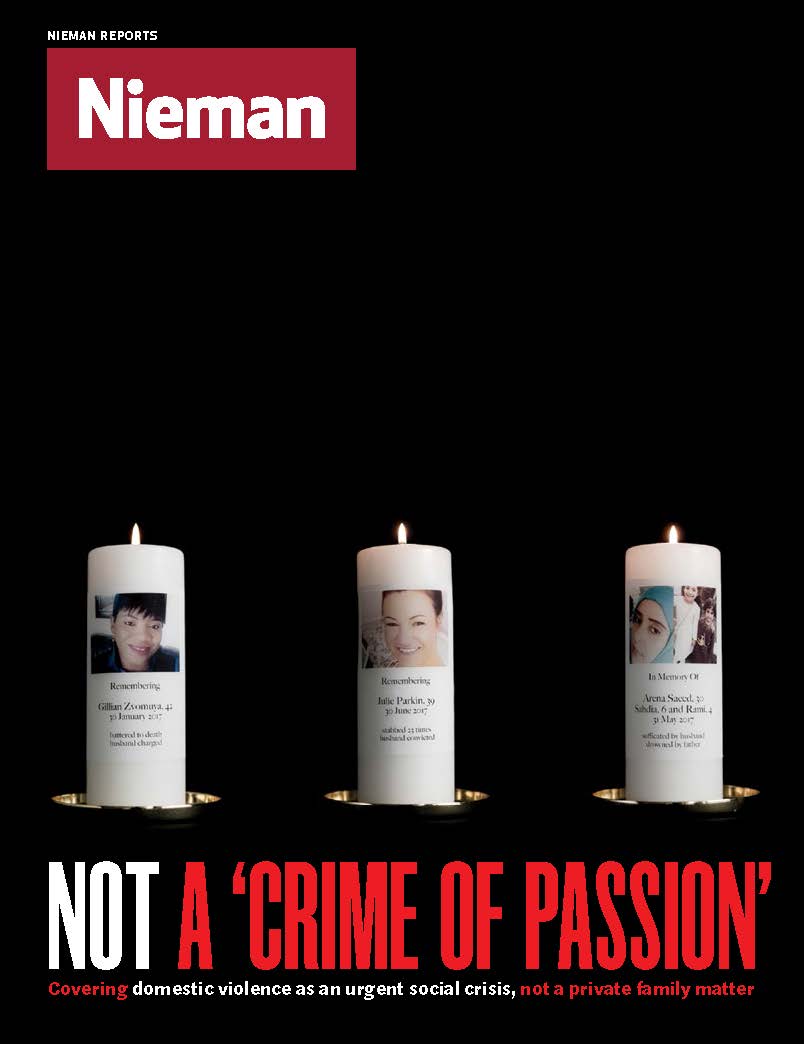

Darrell Jones celebrates with his attorneys after being found not-guilty of a 1985 murder after a judge vacated his earlier conviction. To his right is Lisa Kavanaugh, director of the state's Innocence Program

About five years ago, I received an unusual proposal.

A convicted murderer contacted me to say he wanted to write for the New England Center for Investigative Reporting, the nonprofit news outlet where I work.

Darrell Jones sent a message through his wife that he was uniquely positioned to report on criminal justice because of his 30 years behind bars. He invited me to talk about ideas at the maximum-security Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center, about an hour outside Boston.

I accepted the invitation and took an evening drive to the prison. As we talked in the visiting room, separated by a thin red line taped to the floor, I realized the most interesting story to tell was that of Jones himself. He told me that at age 19, he was wrongly convicted by an all-white jury of a fatal shooting in a Brockton parking lot.

Jones said that the state’s case against him included no physical evidence, motive, or eyewitness who definitively pointed to him in court. Jones was being represented by attorneys from the state’s Innocence Program, a small legal team convinced of his innocence and seeking to re-open his case.

I took the question of whether Jones was innocent to an investigative journalism class I teach at Boston University, where students and professional journalists work side by side. Students learn investigative tools like filing public records requests, reading court records, analyzing data and interviewing reluctant sources while working on real-world stories. Other investigations launched in this class include a focus on the treatment of the state’s aging inmate population and the rising number of student suicides on Massachusetts college campuses.

During the semester, students read court transcripts of the 1986 murder trial and knocked on the doors of witnesses. We broke into groups, each focusing on a topic: The defense attorney who, in connection with charges of stealing from a client, was suspended from work after Jones’ conviction; the eyewitnesses who wouldn’t testify that Jones was the murderer; a deep-dive look at Jones himself.

This was the beginning of the process that went on months after the class disbanded. Some of my students stayed on the team as volunteers.

Leading the group was Leonard Singer, an adult student and Boston attorney who started out as one of the most skeptical and emerged as one of the most dedicated to telling Jones’ story. He spent hours seeking public records, interviewing police and legal sources, and tracking down leads. His classmate Evelyn Martinez, an Emerson College graduate student, also kept chasing leads to those who were near the Brockton parking lot where an alleged drug dealer died by a single shot in 1985.

After the class ended, WBUR news reporters Bruce Gellerman and Jesse Costa joined our partnership to work on the project. They too became engrossed with the hundreds of pages of court records and tackling the critical challenge for radio—finding players in the drama to discuss the case on air.

Gellerman tracked down juror Eleanor Urbati who said that she was never convinced of Jones’ guilt and regrets her decision to go along with the 11 other jurors to convict him. She told us that she believed two jurors were racist—a statement key to Jones’ release.

The investigation led to an award-winning five-part radio and video series and an online print piece.

After the stories ran, Superior Court Justice Thomas McGuire Jr., in a highly unusual move, called back Urbati and other jurors to hear about claims of a racist jury.

Finding the case was tainted by racial bias and police misconduct, he eventually vacated Jones’ murder conviction.

In June of this year, Jones was retried. His attorneys focused on the fact that witnesses described a shooter who was significantly shorter than the victim. Jones, at 6 feet tall, is nearly the same height as the man who was killed. A new, more diverse jury found Jones not guilty after barely two hours of deliberation.

Jones walked out of court on that June day thanking lawyers and journalists who worked on his case for years. He pledged to continue to fight for others still wrongfully in prison.

At a recent event at WBUR’s new Boston venue, CitySpace, Jones talked about his exoneration.

One of his attorneys, John J. Barter, said that when he first reviewed Jones’ case he believed the only way the conviction would be overturned would be if something magical happened. Jones had attempted to re-open his case before and failed.

Barter said magic did arrive: First when the U.S. Supreme Court issued a new decision regarding the right to have jurors without racial prejudice and again when our reporting led to information about such bias. New technology also allowed development of proof that police had altered key evidence and lied about it at the first trial.

Barter clarified that journalists, students, and attorneys weren’t working together. Each of us had our own professional duties. We were each working in our own lanes searching for the truth.

These efforts led to a Boston man’s exoneration after 32 years in prison for a crime he always insisted he didn’t commit. Heading toward the new academic year, I’m excited to think of where our students will focus their attention next.