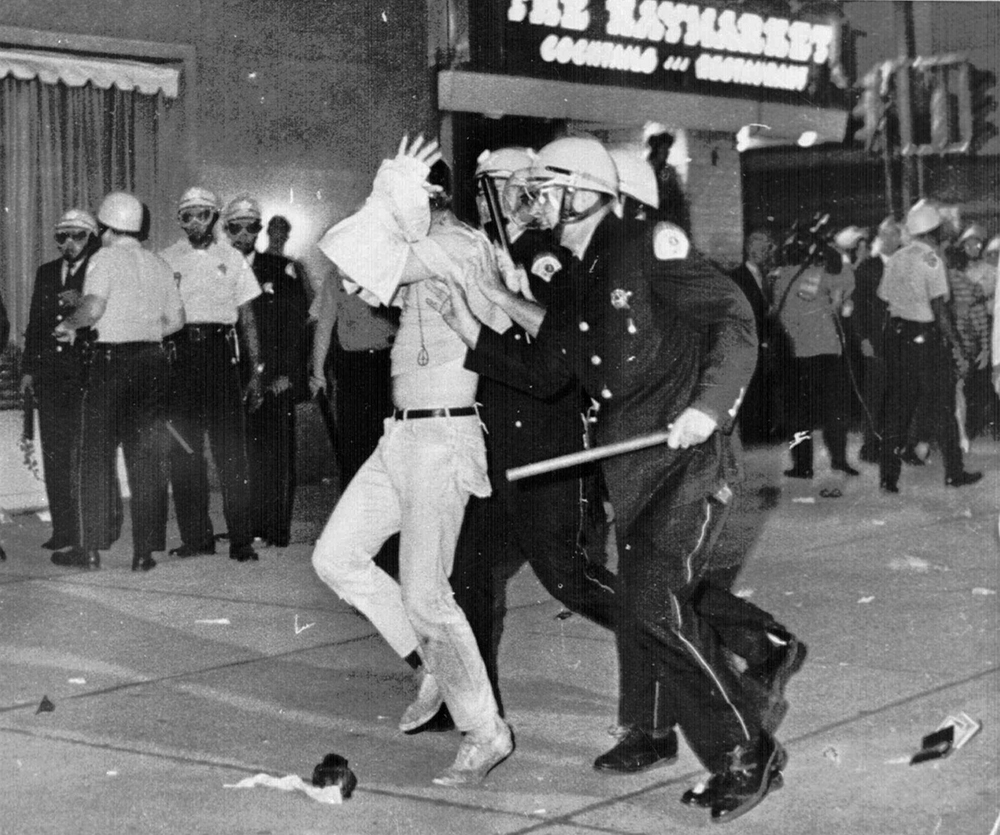

An Aug. 28, 1968 file photo shows a demonstrator with his hands on his head is led by Chicago Police down Michigan Ave. during a confrontation with police and National Guardsmen who battled demonstrators near the Conrad Hilton Hotel, headquarters for the Democratic National Convention

Heather Hendershot’s most recent book is “Open to Debate: How William F. Buckley Put Liberal America on the Firing Line,” which one review described as “a thoroughly researched work replete with intelligence, admiration, balanced criticism, and even a bit of nostalgia.” Nostalgia is an apt description, she says, calling Buckley’s public affairs TV show “Firing Line” “a place of reasoned thoughtful debate between left and right for a good 30 years.”

Heather Hendershot

A professor of film and media in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing Program, Hendershot is now researching a book about 1968—“one of the most troubled years in the history of America,” she calls it—and coverage of the violence at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August. Many photographs from those days have become iconic and, Hendershot says, it’s important to revisit and reinterpret what happened in part because many Americans have sharply divergent understandings about the events. She spoke at the Nieman Foundation in March. Edited excerpts:

On Cronkite’s coverage of the Vietnam War

It’s so fascinating to me that CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite was attacked for his coverage in Chicago but right before it he had done a very famous broadcast on Vietnam. He had gone to Vietnam in 1965 and was toeing the government’s line about how things were going in Vietnam. He was not atypical in this. The mass media was reporting what the government told them was going on in Vietnam. He was a liberal hawk, in a way. He wasn’t against the Vietnam War in’65.

In 1968, the Tet Offensive happens and he goes back to Vietnam in February. He returns and he says, “I think if we examine this carefully, we have to see that there’s a stalemate in Vietnam. We’re just not going to win and the best thing we can do is get out.” He was very concerned that this would be seen as biased and he framed it very carefully. He didn’t do it on the evening news; he did it in a special report on Vietnam. It was framed by his sense of professional responsibility.

CBS was not deluged with letters after this happened. While some right-wingers were of course disturbed, the general sense among viewers was that he had bent over backward to be as unbiased as he could be.

On coverage of the ’68 Chicago protests

Mayor [Richard J.] Daley was prepared for 10,000 protesters to come to Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. He had easily double that amount of security forces—National Guardsmen, policemen, and so on. He made the town into a fortress and set things up for the police to take violent action, which they did. The federal government investigated later and declared that what had happened in Chicago was a police riot.

After the worst night of violence, the television networks got telegrams all night attacking them for how they had covered the violence, attacking them and accusing them of liberal bias. For what? For showing what happened in the street? Well, for not showing how the protesters deserved to be attacked, for not showing protesters committing acts of violence (and hurling profanities) for which the police were retaliating. They were attacked for calling the protesters “protesters” instead of “terrorists,” which was what Mayor Daley wanted them called. They were attacked for calling them “young people.”

Cronkite felt that he and his team had done a good job as journalists, but he can’t stand being called biased and unobjective. He gets an interview with Daley the very next day, before the convention starts up again, to show that he’s fair and balanced and to show the nation that they’re trying to provide equal coverage to both sides. It also is at a moment when the Fairness Doctrine is still in place, which says that broadcasters have to cover controversial issues of public importance and when they do so, they must show both sides of the issue. There are assumed to be two sides to any controversial issue.

Cronkite is responding to these accusations of bias specifically out of this Federal Communications Commission moment of regulation before the Reagan administration deregulated the communications industry, among other industries, in the 1980s and eliminated the Fairness Doctrine. After remarking on how friendly the police had been in the days before the violence, Cronkite tells Daley “There shouldn’t be any reason we can’t be friends.” It was basically a low point of Cronkite’s career and even he acknowledged that later.

The exchange between Cronkite and Daley is useful to watch on so many different levels. One of them is that we have a nostalgia for the era before Fox News, MSNBC, Internet, blogging, and social media. We have a nostalgia for how things used to be better in the past. In many ways, it was better. But I think that the Cronkite-Daley interview points to the phoniness of some of this cordiality of the network news era where you’re trying to make nice, not violate the Fairness Doctrine, show that you’re impartial and balanced and so on, and the result in this case was pretty disastrous.

On charges of “liberal media bias”

Cronkite, the big voice of the network news media, was widely seen as the most trusted man in America. Even though he was privately a liberal, Cronkite was generally seen as very neutral as a broadcaster. Except for people on the far extreme right, even conservatives were like, “Yeah, he’s liberal technically, but he’s neutral because that’s his job as a reporter.”

The idea of a broad popular opinion that a newscaster was biased was foreign in many ways to that moment. This idea of liberal media bias did have roots in attacks on media coverage of the civil rights movement, but I do feel that’68 was a moment when it got nationalized as something that conservatives were concerned about as opposed to it being a more regional Southern thing.

Somehow the tipping point was this extended moment of violence in the streets of Chicago where people were like, this is where Cronkite has gone too far. This is where Chet Huntley and David Brinkley on NBC have gone too far, and it took hold.

Then Richard Nixon comes along, and his vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, digs into the media for him and attacks them for bias, calling them “nattering nabobs of negativity.” He’s doing Nixon’s dirty work in attacking the media. It helps the notion of liberal media bias spread roots and root, if you will, into the mainstream consciousness and into the right.

There was very little standing up for CBS and for the networks at the time. What you find in the letters and the telegrams that go to Cronkite is a lot of the people saying, “I’m a liberal but…” which is interesting. It’s like they reached some kind of breaking point with the counterculture and the Vietnam War protest, and somehow some of these people who had identified as liberals would come to understand themselves as part of the Silent Majority that Nixon named.

You do not find many liberal voices in the CBS Evening News archive, and they saved every letter—it’s a damn good archive—standing up for the DNC coverage. They somehow accepted that something had gone wrong in Chicago and that the problem was with the news media, which is bizarre. I can’t explain it.

On Daley having his say

After the convention, the networks keep getting complaint letters. CBS got almost 9,000 complaint letters in the first month or so, and they ran 11-to-1 against CBS. Daley goes to the networks and says, “I want some free airtime to respond to your biased coverage.” NBC says, “You can come on ‘Meet the Press.’” CBS says, “No, we already gave you that interview and it was really softball and you’ve had your say.” Daley rejected the “Meet the Press” offer. He didn’t say why but it was obvious he was a poor debater and public speaker. He always used malapropisms, so it was embarrassing. He didn’t want to have a discussion on“Meet the Press,” he wanted to give them a talking head film so that they could just show his perspective that the police had behaved admirably during the convention.

He didn’t get that free network time that he wanted. He decided to put out a magazine—his report of what happened—for Chicago. His telling of the story was managed by his press secretary, who edited the publication, and who also supervised the production of a one-hour film that did end up getting some national airtime. The publication made fun of the protesters and their street theater, tried to show them as freakish. There were moments of misfire. For example, there was an image designed to show that the protestors were repellent and terrible people attacking the police. It’s a man screaming and anchoring himself to a lamp pole as all these National Guardsmen come at him with rifles. Many people seeing this would feel a sympathy with the protester, not with the National Guardsmen. But Daley was so clear in his mind that the protestors were just monsters that he didn’t even imagine that counter-interpretation of this image.