In the four years since the end of my 14-month tenure as editor of the Los Angeles Times, the nation’s largest metropolitan daily newspaper, I’ve given a lot of thought to what I would do now with the resources I had available to me back then.

There’s no doubt that I would change the way I would use the 920 journalists and the $121 million budget I had at my disposal. I thought then—and I still think—that the Times should give readers something they need and want—systematic, stellar coverage of California, which is as big and more important than many nations.

As editor of the Times, I didn’t get to talk to as many readers as I would have liked. But whenever I did, they all said the same thing: They needed better and more sophisticated coverage of the state, a role that plays to the strength of the Times.

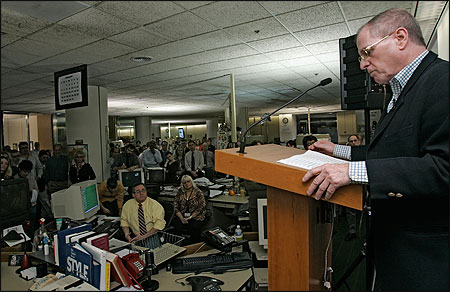

Los Angeles Times editor James O’Shea addresses the newsroom before leaving the paper in 2008. Photos by Kevork Djansezian/The Associated Press (top); Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times. Copyright © 2008 Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with permission (bottom).

The paper was considered one of the industry’s crown jewels. We had everything a multimedia newsroom needed: news bureaus around the world and nation, great correspondents and editors, stunning photography, sophisticated graphics, and strong, solid reporting.

But the organization lacked a crucial component: It had a weak sense of community, the core of its journalistic soul. In fact, few in the organization could even agree on which community the paper should serve. Many journalists felt that the Times community was the nation and the paper had to be the voice of the West.

The marketing and advertising departments argued that the Times should be a local paper, one that provided the region’s cities and towns with intensely local news coverage. Never mind that such a goal was impossible. Even if I had closed all of our foreign and national bureaus and diverted the resources to covering places like Temecula, the paper still would have needed an infusion of cash that was not available. Los Angeles County alone has 141 cities, towns and census-designated places.

Lost in the confusion generated by the second-guessing and internecine warfare common to organizations under such stress were key existential questions: What was our purpose? Just who was our community and what did our community expect of us?

News organizations exist to serve the community by providing credible information so citizens can make informed decisions, the lifeblood of a democracy. Each newspaper has a different community. What might work for the Los Angeles Times won’t necessarily work for the Chicago Tribune and vice versa. But a news organization must determine how it can best use its journalism to serve the public, where it can fill gaps in public knowledge that will give it a leadership role in the community. If it does a good job and gives the community information it can’t get elsewhere, the newspaper, website, magazine or whatever can charge more because it is truly adding value.

The Los Angeles Times is still uniquely positioned to fill a huge public need—aggressive coverage of California, a state with problems that equal its heft, a state hit particularly hard by the recession and the toxic mortgage scandal.

The success of California Watch, an online project of the Center for Investigative Journalism in Berkeley, is evidence of the interest in this kind of reporting. Media outlets throughout California have snapped up California Watch reports on state issues. There’s plenty of room for more.

Three Critical Skills

RELATED ARTICLE

“The Great Young Hope”

– James O’SheaOnce I set my eyes on state coverage, I would become radical in my approach. The Times newsroom—and, for that matter, the entire news business—needs to be totally reorganized to revolve around three skill sets.

The first and most basic set is technological. Most journalists of my era and earlier know little about things such as data mining and geotagging. This is technology that, in the right hands, can be used to monitor and analyze communities and make it possible to dramatically expand the reach of reporting deep into those communities. Public records can be mined for information about everything from health outcomes to real estate transactions.

The second skill set—and the one that is more important than ever—is the ability of the journalist to report and analyze. Raw data can be interesting, but it assumes value when a skilled journalist uses reporting to turn it into credible knowledge or insight.

Data can tell you which hospital in Los Angeles has the best outcomes for heart surgery. But it takes reporting and editing to tell you why that hospital is best. Does it excel because it has top-quality physicians, more specialized nurses, certain best practices, or what? Those are the kinds of questions that journalists know how to probe and answer.

The third skill set is social media experience. Newsrooms need experts in social media to determine who in the community wants this journalist-enhanced data and how best to get it to them. Social media experts can also help connect journalists directly to the community, bring others—be they bloggers or citizens—into the conversation, and promote the kind of honesty and standards that makes for distinguished journalism.

I can’t say precisely how I would realign my staff and resources to populate the ranks of the new newsroom. But it wouldn’t be that hard. And I know it would take some new investment to provide the kind of training and education that currently doesn’t exist. Lastly, I would lead a crusade to convince journalists in the newsroom that they can no longer expect someone else to solve their problems. Journalists of my era often responded to the challenges posed by the industry’s shifting business model with the retort: “That’s a business side problem.” More often than not, though, the business side’s answer was budget cuts that diminished journalism. Tomorrow’s newsroom leaders must take responsibility for the success of the enterprise by convincing themselves, readers and owners alike of something that has always been true: Good journalism is good business.

James O’Shea, editor of the Chicago News Cooperative, is the former editor of the Los Angeles Times and the author of “The Deal From Hell: How Moguls and Wall Street Plundered Great American Newspapers.”